Bill, an Australian traveler in Zimbabwe, stood in the velvet-caped darkness and listened. I planted myself next to him and sucked in my breath, not wanting the smallest leak of air to disturb the quiet. And then we waited for it, the low growl that would confirm our suspicions: A lion had crashed our campsite.

After hearing the noise again, I grabbed our guide from the picnic shelter. Onary screwed up his face as he registered the bellow. Then his expression relaxed, and he let out a belly laugh.

On a budget safari in Africa, I was out in the raw elements, among the wildlife and the humans who snort like them. I couldn't shush either one, a concession I had made for the savings I had reaped by roughing it. But what I sacrificed in soundproof accommodations, I gained in adventure and adrenaline-including the thrill (real or imagined) of a predator within a whisker of my tent flap.

Several companies offer overland safaris that keep costs down by swapping in camping, campground cooking and bus transport for pricier lodges, restaurants and bush planes. (Higher-end safaris typically cost $400 to $1,000 a day.) Intrepid Travel, for one, lists three levels of comfort, with "Basix" at the bottom. Before signing up for this nine-day trip from Victoria Falls, on the border of Zambia and Zimbabwe, to Kruger National Park in South Africa, I had to look deep into my travel soul and ask: Was I looking for an "exceptional value" and "plenty of free time?" Yes, I was. Did I want the "flexibility to choose where and how [my] time and money was spent?" I certainly did. Could I handle early rises, long drives on rutted roads and such duties as food prep, kitchen cleanup and tent assembly? For $1,100 (land only) and the possibility of seeing a leopard or a lion, roll out the sleeping bag and toss me the potato peeler.

Intrepid Travel copies the pricing model of a low-fare airline. The company provides the main elements-tents with sleeping pads, most meals, safari truck transport and a few game drives-but you pay for the extras, such as a sleeping bag (you can also bring your own) and optional tours. At Victoria Falls, our starting point, the excursions included a gorge swing for $110 and a 12-minute helicopter flight for $180. The Irish teachers in our group splurged on the heli ride; I opted for a lower and less expensive view of the falls, paying $30 to enter the park. I could have rented a raincoat, but I knew that the wait for a hot shower at the campsite could be long, and my fallback plan was the largest waterfall in the world.

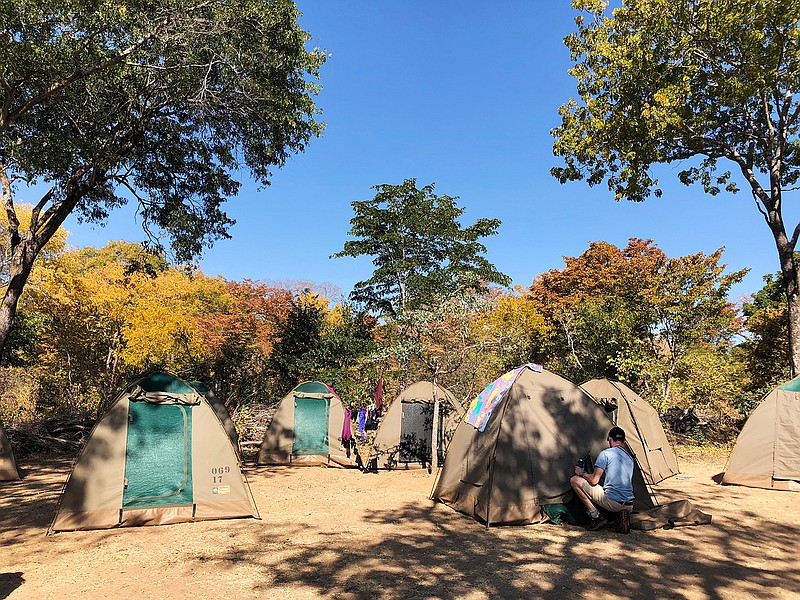

When I showed up at the Victoria Falls Rest Camp, our rendezvous spot in Zimbabwe, the tents were already standing. All I had to do was toss my bags inside and remember which tan-and-green shelter was mine. That evening, we met each other (14 people, five nationalities, a half-century age span) and the staff. Onary, the guide, introduced us to Enos, the cook; Ernest; the driver; and Truck, the truck.

"This is the fourth member of the crew," Onary said of the 24-seat vehicle. "Treat it with respect. If he breaks, he's not going to take us where we need to be."

Onary, who grew up in Zimbabwe, briefed us on the itinerary. We would spend four nights in Zimbabwe, one night in Botswana and three in South Africa, and were responsible for buying five lunches. Since we would be traveling in close and sometimes challenging quarters, he encouraged us to "develop a family spirit and have space for others in your minds and hearts." He also urged us to not contract malaria.

"You paid for the trip to enjoy, not to get upset," he added philosophically.

I raised my hand with a few questions. Since I had paid a single supplement of $72, could I have two sleeping pads, for my phantom other half? The answer was no. Did we have drinking water? No. Onary said the staff fills jugs with tap water, but the company's pre-departure notes warned us to avoid water from the faucets, a common concern in developing countries. After he wrapped up the talk, reminding us of the 8 a.m. departure time, we streamed into town and hit up the OK supermarket, loading up on chips, biscuits and five-liter bottles of water.

Dinner was not included that night, so three of us scanned the menu at a fast-food joint. Bill and Ash, a British cook, poked at fried chicken that looked tragically undercooked. I settled on a liquid dinner of red wine and instant coffee provided by a South African family camping between my tent and the bathroom. Our meeting was inevitable.

You never forget your first wildlife sighting. Mine was a pair of vervet monkeys goofing around at Victoria Falls and a lone warthog snuffling through plastic outside the national park's entrance. The next day, I added baboons, but fortunately not during what our guide referred to as a "bushie-bushie" stop.

"They're going to see you once and never again," Onary said of possible run-ins-whether simian or human-during the roadside bathroom breaks.

On the half-day drive from Victoria Falls to Hwange National Park, we stopped in the nearest town for supplies. More chips, more water, but no coal, the area's main industry. I walked around the commercial strip, passing several banks that appeared dark and empty in a sign of Zimbabwe's financial distress. The following day, in Bulawayo, the country's second-largest city, we would see people lined up hoping to withdraw their $30 daily allotment before the currency stream dried up.

When we arrived at the Ivory Lodge Campsite, we moved like ants, quickly raising our tent village. After lunch, several of us climbed up to the observation deck overlooking a watering hole. Dozens of elephants appeared from out of the bush. A voice from down the road hollered for us to come down. We followed a dusty path to an elegant lodge, where a guide led us to a sunken teak lounge with an open window and an intimate view of the elephants. We were so close I could see the tufts of hair on a baby elephant's head and follow the watchful eye of its protective mother. After several minutes, the employee ushered us out, just as the paying guests pulled up.

"Look what we ordered for you," he informed his excited clients, directing their gaze to the herd.

We trudged back to camp, smug in our knowledge that we had seen them first.

That afternoon, we boarded two open-air vehicles for our first official game drive. The Hwange park guide, Zebedee, told us to call him "Rhino," though his name was not prophetic. A better nickname would have been "Impala."

Back at the campsite, with images of wild animals dancing around in our heads, Onary told us to stash our shoes inside our tents. Hyenas and jackals might snack on them while we slept, or scorpions could burrow inside. That night, all footwear remained indoors.

Rhinos are better than caffeine.

If you are feeling drowsy, as I was after a cold night of camping and an early wake-up call, seeing the horned animals lolling around in the grass will revive you faster than a double shot of espresso.

We started the overcast morning outside the gates of Matobo National Park, where our guide Kurt Schmidt described the event that sparked his interest in rhinos.

"I was charged by a black rhino," he said.

The harrowing incident drew him closer to the animals, inspiring him to learn more about their behaviors and to tighten his protective arms around them. With a 95 percent unemployment rate in Zimbabwe, poaching is pervasive. He asked our group to not publicize the park's rhino population numbers and to turn off the GPS feature if we planned to post photos of the rhinos. He didn't want to give poachers any leads.

Kurt was less guarded about the black eagles (200 breeding pairs) and the leopards (600) inhabiting the park.

"They are ambush predators," he said of the big cats. "It's wonderful to know that we are being watched."

While explaining dehorning and his controversial idea to legalize rhino horn, he received a call.

"Fantastic! That's good news," he said into the receiver. "Guys, we have a rhino to look at."

On the trail, he told us to walk in single file and remain quiet. We stopped at a clearing, where I could see patches of tough gray skin but no distinguishing features. Then the blobs were gone, disturbed by our presence.

Not giving up, we scaled a rocky incline and looked down to find our quartet. From this vantage, we could see the white rhinos in various stages of relaxing-not the most scintillating activity if you're watching a cow but fascinating if your object of interest is a prehistoric-looking beast. Kurt motioned for us to follow him down the hill and around the bend, for a ground-level view. He smacked his lips, hissed and released a high-pitched, nasal sound. The rhinos twitched their ears.

"We are trying to tell them, 'We are here and one of you.' " he explained.

The sky was darkening and the temperature was dropping, but we had one more stop before we returned to the campground. We disembarked in a small village and entered the thatch-roofed home of a Ndebele chief. In his native language, Pondo entertained us with the story of his first leopard hunt, an animated tale that involved a dog, a good Samaritan in a pickup truck and a trip to the hospital. (Kurt acted as translator.) The 87-year-old, who wore a quill bib and plumed headgear, also told us about his trip to South Africa in the 1960s. He was responsible for transporting eight white rhinos to the park. Based on his animated actions, all bent knees and grunts, it was a colossal job.

Pondo asked us to join him in a prayer for rain and a good harvest. Then, he invited us to take photos with him in matching leopard skins. I skipped the photo op and played with the children instead. We snapped selfies and I showed them videos of penguins. A boy named Mpendulo sketched a picture of a rhino in my notepad. I asked him if he had any other drawings. He presented me with a stack of images of the animals, landscape and people that are part of his daily life-and are now a part of mine, too.

I saved money. Botswana waived its visa requirement days before we arrived at the border crossing. Also, because we were traveling during peak season, Onary was not able to reserve seats on an optional evening game drive in Kruger National Park in northeastern South Africa.

I also spent money, in the name of staying warm. I bought a blanket and sweatpants in Botswana and upgraded to a bungalow at our overnight in South Africa's Limpopo province. (Many of the campgrounds provide indoor lodgings for an extra fee. Emma, an Aussie, and I each paid $15 for accommodations with two beds and a bucket shower but no electricity.) For our final safari, I tossed frugality to the lions.

We had one full day in Kruger, and Onary advised us to skip the open-air vehicle, which cost extra, and ride in the truck, which did not.

"You pay 880 rand [about $60] for the day drive and you don't see anything," he said, "and then you come back with your faces down."

We were one of the first vehicles through the gate, and less than 10 minutes inside the park, we were gazing at impalas, elephants and more elephants, guinea fowl, black-chested snake eagles, Cape buffaloes, hippos, crocodiles, lilac-breasted rollers, zebras-and Zazu from "The Lion King," otherwise known as a red-billed hornbill. Just after 10 a.m., we released a communal gasp when we spotted a leopard about 300 feet from the road.

"This is very, very, very rare," Onary said. "He is in a hunting position, relaxing and conserving his energy in case something happens past."

Post-leopard, we checked off waterbuck, tawny eagle (a pair), giraffe and kudzu. Someone yelled out "lion," but it was a false alarm. We glared at the rock.

In the late afternoon, we piled into jeeps for the second half of the safari. Onary had originally quoted us a price of $25 but later informed us that the fee had nearly doubled. A few of us groused, but in the end, we paid up.

"Please find us a lion," Niamh, an Irish teacher living in Abu Dhabi, implored the local guide behind the wheel.

He complied. He darted through the bush, screeching around corners and pummeling the vegetation. Without warning, he turned off the engine and pointed at our prize: a male teenage lion commandeering a hill. For several minutes, we had a private audience with a lion, an experience that temporarily made us forget all the rest.