The Gloria Allred everyone knows would jump at the opportunity to be the subject of a film. This is the attorney, after all, who for decades has invited reporters to her law firm to publicize press conferences where she dutifully comforts clients in front of cameras for maximum impact. The woman who has been deemed an ambulance chaser by exploiting the cult of celebrity, representing women allegedly maligned by some of Hollywood's most notorious names-Bill Cosby, Charlie Sheen, Harvey Weinstein.

And yet it took the filmmakers behind the Netflix documentary "Seeing Allred" three years to persuade the lawyer to tell her own story.

"We had to do some work so that she trusted that we really were on her side-that our questions weren't salacious," explained Marta Kauffman, who produced the movie. "We were really trying to understand who this woman was and how she ended up being such an incredible fighter for change and justice."

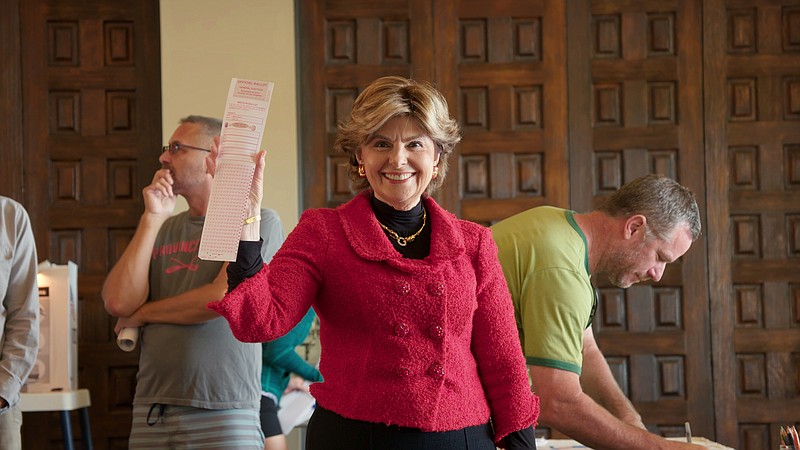

Dressed in one of her impossibly bright power suits at the Sundance Film Festival last month, where she had traveled to premiere "Seeing Allred," the 76-year-old Allred insisted that she was mainly reluctant to sign onto the project because she feared breaking attorney-client privilege. When she did agree to participate, she said, she was uncomfortable when the focus fell more on her than on her clients-"the victims, the heroes"-whom she cites as the only reason she signed onto the film at all.

"They were ultimately able to get to me to talk a little about my life," Allred said of the movie's two directors, Roberta Grossman and Sophie Sartain. "Not as much as they would have liked. More than I would have liked."

Coming from an established master of calculation, that may sound like a load of hogwash. But when Allred sits for interviews in the film, nearly all of which take place in her glass-walled Malibu mansion overlooking the Pacific, you can see her stiffen any time the questions take a turn toward the personal.

When Grossman inquires about her contentious 1987 divorce from her second husband, William Allred-"we're wondering if that was a hard time for you?"-Gloria pauses to come up with a diplomatic answer.

"I've had challenges that were greater than that one," she responds.

"Judge," Grossman says, "could you please tell your client that she's being non-responsive?"

PERSONAL MOMENTS

The directors did manage to get Allred to open up about some intimate moments in her life. The film's most harrowing sections reveal that at age 25 Allred was held at gunpoint and raped while on vacation in Mexico. After the sexual assault, she became pregnant and was forced to get an illegal abortion that sent her to intensive care with a 106-degree fever. While hemorrhaging, she said, a nurse told her: "This will teach you a lesson."

"I didn't want to really talk to anybody about it," Allred tells Grossman of the assault.

"Wasn't it hard not to talk about it?" the director replies.

"It's not hard for me not to talk to people about things," the lawyer responds.

Sitting across from Allred, it's clear just how true this is. She can certainly be long-winded and is happy to stick to what feel like talking points, such as her effort to change the statute of limitations for sex crimes or how the #MeToo movement has ushered in the Age of Empowerment.

"We won change, that's the point. And that's what I want people to see in the film," Allred said of the documentary landing just as #MeToo and #TimesUp have become global buzzwords. "You don't have to say, 'I'm depressed by what happened to me.' Because that's rage turned inward. And I want rage turned outward. I don't want women to be tranquilized out of their rage."

But just when you think you're getting close to breaking past her brusque exterior-maybe she laughs or seems genuinely surprised by a question-she can shut you down in a way that feels impossible to overcome.

That's what happens when it comes to the subject of her daughter, Lisa Bloom. For years, the mother and daughter have been exceptionally close. The documentary explores the lengths to which Allred went to provide for Bloom as a single mother, working as a teacher during the day, subbing at the Cerebral Palsy foundation two nights a week and commuting from Philadelphia to New York twice a week to pursue her master's degree.

"I didn't get my child support, so it was like 'OK, I'm responsible. I have to step up. I have to do it,'" Allred recalled. "My motivation is out of necessity. Just do it. Don't complain. My father worked 12 hours a day, six days a week and on the seventh he prepared for the next six. He had to take care of my mother and me. So that's what he did, and that's what I do."

As an adult, Bloom would go on to follow in her mother's footsteps, even working at Allred's firm for a spell and advocating on behalf of women. But in October, when Bloom began representing Harvey Weinstein against allegations of sexual assault, Allred publicly spoke out against her daughter. She released a statement saying she would never have worked with Weinstein but would "consider representing anyone who accused Mr. Weinstein of sexual harassment, even if it meant that my daughter was the opposing counsel."

Though Allred later walked back her comments-writing on Facebook that "I stand behind Lisa and support her"-the damage was done. In an interview with The Times last fall, Bloom expressed her hurt over the remarks, noting that it would take a while for the relationship to heal.

Asked at Sundance about the state of their relationship, however, Allred bristled.

"I have no comment about that except to say that I love my daughter," she said. "I'm in communication with my daughter. I'm very proud of my daughter and how she stands up for women's rights."

Bloom is a big part of "Seeing Allred," appearing in numerous clips talking about her upbringing. Though she spent years "answering questions, looking for old photos and sitting for several interviews," Bloom said, she has yet to see the documentary and was not invited to the premiere. (The filmmakers did not respond to a request to verify what Bloom said.)

"(I)t would have been cool if someone had sent me a copy," Bloom wrote in an email last week, noting that her mother has not called her since she "publicly attacked" her in October. "Anyway, I hear it's good. She deserves the recognition for her life's work advancing women's rights."

BLAZING A TRAIL

Indeed, the documentary, which has received glowing reviews from critics, does an excellent job of synthesizing Allred's importance to the feminist movement. Even her recent work-re-presenting 33 women who allege they are victims of Cosby-blazed a trail for accusers to feel comfortable speaking out.

"Reporters were asking me after I did some of the press conferences with the (Cosby accusers), 'What's your end game, Gloria?' I always felt that this was a process," Allred said. "I didn't know if he would ever be criminally prosecuted. I didn't know if we would ever change the law. But I felt that through the process, persons who alleged that they were victims and were telling what they said was the truth about their lives would become empowered.

"There is something that happens to women and to victims when they can speak out. Even if nothing happened beyond that, that would be inspiring to others. And that's what happened. More women came forward. More and more and more."

But as "Seeing Allred" points out, the lawyer has a long history of fighting for equal rights.

In 1995, she took on the Boy Scouts of America when they wouldn't admit an 11-year-old girl into their ranks. In 1997, she helped soap opera actress Hunter Tylo win a $4.8-million judgment after Aaron Spelling fired her from "Melrose Place" because she was pregnant. And in 2004, her firm filed the first lawsuit in California arguing that it was unconstitutional to deny same-sex couples marriage licenses.

"It isn't until you sit down with her that you go, 'This is not the woman I saw on TV,'" said Kauffman, the producer. "And I have to say, I feel guilty about that. I think one of the reasons people love to hate on Gloria is that she is the metaphor for the entire feminist movement-thinking back to the suffragettes. All the women who speak out are brash, loud, strident, trying to be men-and she's sort of the metaphor for it. So the ability to really show what's underneath it hopefully has an effect on how people feel about feminists and justice."

The film also explores how the tireless work ethic Allred inherited from her parents-"they only had an eighth-grade education," she points out-continues today. She spends most of her nights and weekends working, always whipping out her laptop during a spare moment of downtime at the airport. She is hardly ever seen in public without one of her pricey blazers or a full face of makeup. She has not been in a serious romantic relationship in decades. And her skin? It's only gotten thicker through the years.

"Look, people can call me names," Allred said. "Like in 'Gone With the Wind': 'Frankly, Scarlett, I don't give a damn.' So, no, that's not a weapon that can be used against me. It's ineffective. Much to the chagrin of some people who would like it to stop me.

"There's nothing stopping me until I win justice and then I'll stop, OK? Until that day, I'll keep on keeping on, because that's my duty. That's what I owe to women."