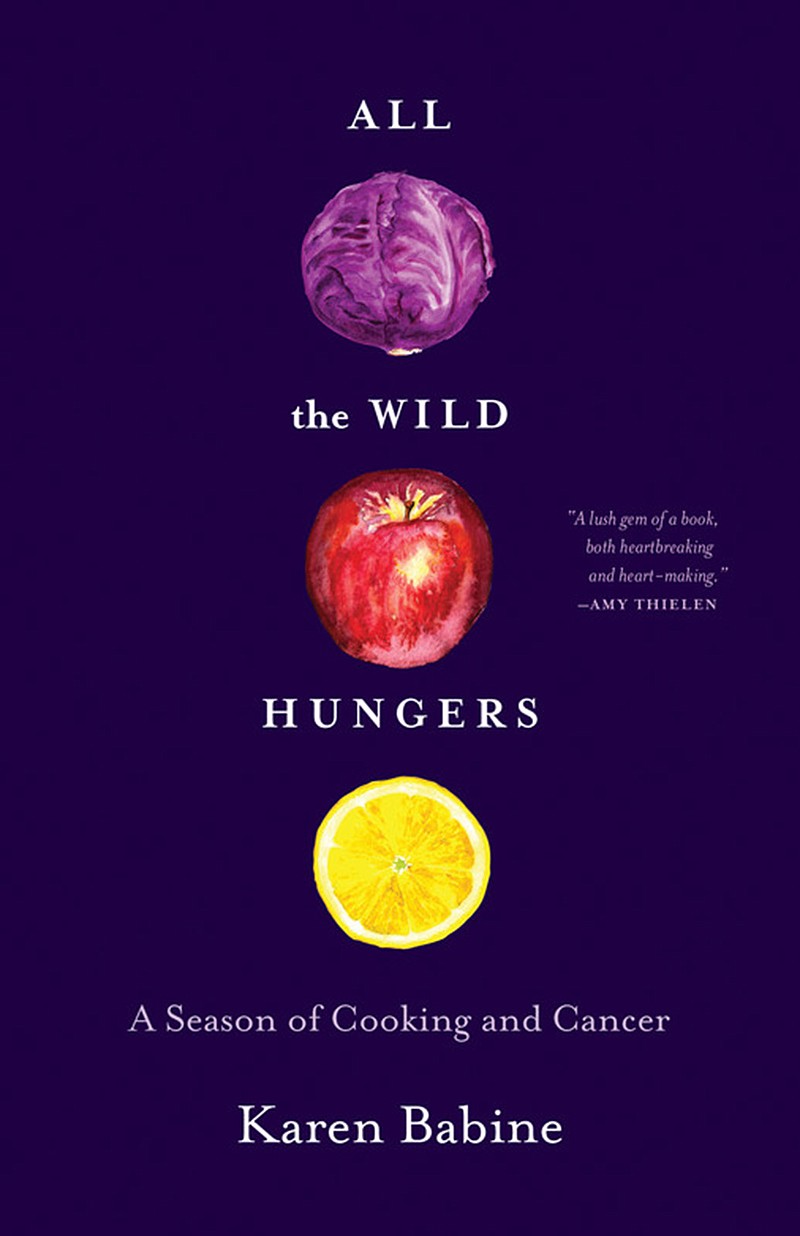

Life at its most priceless-not its dramatic, headline-making moments, but the quiet but potent joys of daily life, such as cooking new dishes in the family kitchen, doting on sweet nieces and nephews, and caring for an ailing parent-is the subject of writer Karen Babine's beautiful "All the Wild Hungers."

Life, yes. But death, or its inevitability, hovers over every page, a wolf at the door of the warm, aromatic kitchen. The book is a memoir of Babine's time caring for her mother, Barbara Babine, who developed a spooky form of cancer called embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, in which the malignant cells resemble the developing skeletal muscles of an embryo. If ever there were an ailment that reminds us of what vulnerable mammals we are, this was it.

Karen, one of three daughters of Barbara, a longtime and beloved fourth-grade teacher, along with her pastor father and her sisters, brother-in-law and wee niece and nephew, rally around Barbara as she undergoes chemotherapy. There is such mercilessness and cruelty in the cancer, yet such mighty love in this family.

Babine finds comfort in almost obsessive cooking. Almost daily, she employs her collection of antique cast-iron pots, scavenged from antique stores and flea markets, to concoct dishes that are spectacular and soothing. Through patience and practice, she is able to discover some foods that her nauseated mother can stomach, food that gives her strength and hope.

Anyone who has experienced a family member's struggle with cancer will be stabbed by recognition throughout this book, as when Babine writes, "We don't ask, how are you doing? anymore-we ask, how is today?"

Babine is a Minnesotan to the core. She writes about the comfort food loved by Swedish-German-American families, and about going to Hackenmueller's Meats in Robbinsdale, where she, a somewhat sheepish vegetarian, is offered kind and wise advice, and the very best ingredients, for making bone broth for her protein-deprived mother.

At book's end, Babine's mother is in remission, but the kind of cancer she has is not easily derailed, and so it is no surprise to google Barbara Babine and find that she died on Nov. 1 of last year at age 68 in New Hope. It hurts to read that, because Karen's love for her mom, which runs like an artery through this book, is infectious.

There are some profound passages in this memoir. At one juncture, Babine ponders the recently discovered science of fetal microchimerism, "the phenomenon of fetal cells being found in the mother decades after birth," and writes, "Are we our own unique beings or not? Science would suggest we are not. We exist within systems, networks, the matrix of family and friends, patterns. We are not alone. We are all connected, even on a cellular level, across time, space, and logic. Perhaps it is individuality that is the myth."

In the end, the overriding hunger referred to in this lovely book's title is the hunger for life. Perhaps it is never stronger than in the shadow of death, and in the light of death's opposite, love.

Praise, sympathy and thanks to Babine, who has given us this ode, lament and meditation.