Today, they're known as Jeju Island Mermaids. On the South Korean island, one of that country's major tourist destinations, the women are a charming historical attraction.

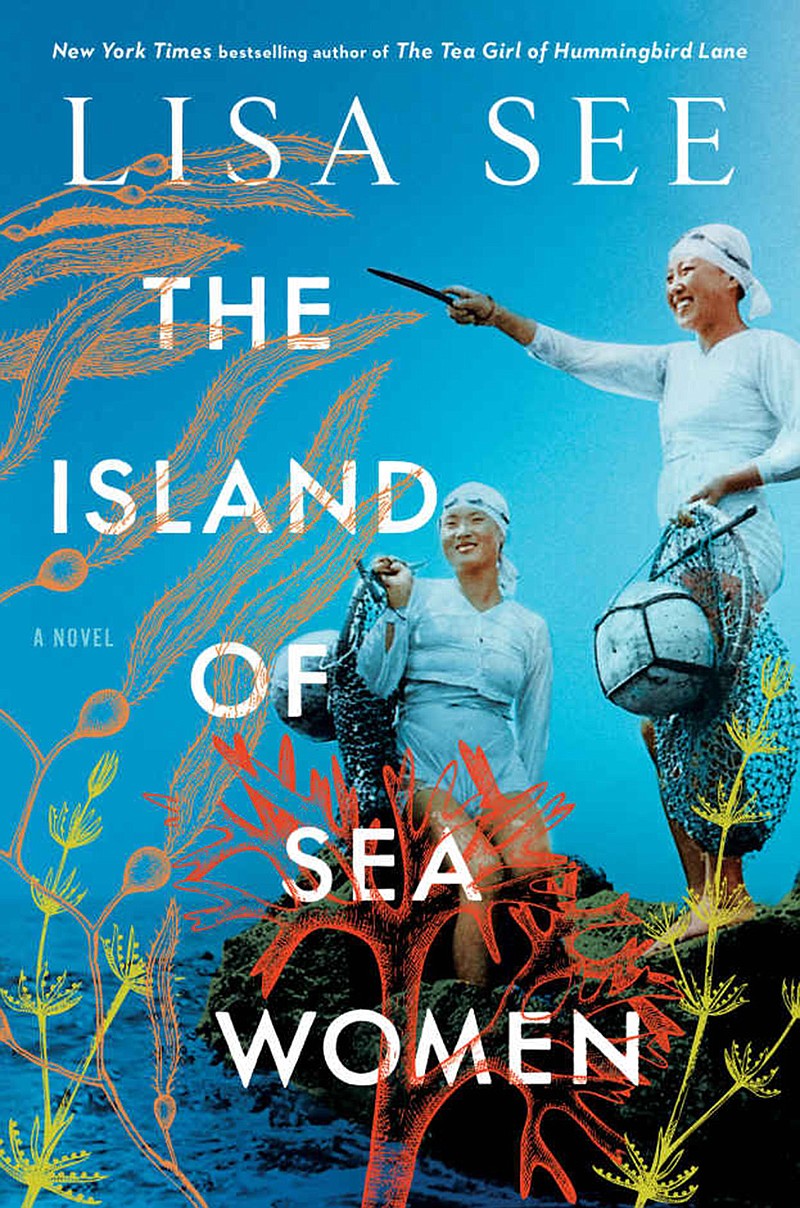

Lisa See's new novel, "The Island of Sea Women," brings that amazing history to life. For generations the "mermaids," called haenyeo, supported their families by freediving deep into the ocean to harvest its bounty. Their husbands stayed home and raised the children, and the culture was matriarchal.

In the book's first chapter, set in 2008, we meet Young-sook. Now 85, she has been a haenyeo since she was 15, like her mother and grandmother before her. A great-grandmother herself, she no longer has to dive for a living, but she can't stay away long from "the weightlessness of the sea, the surge that massages the aches in her muscles."

While sitting on a Jeju Island beach, Young-sook is approached by a family of American tourists: a white husband, a Korean wife and two "half-and-half children." Their identity and their reason for seeking her out will plunge the novel into the story of her long and eventful life.

See has written several deeply researched and best-selling historical novels set in Asia, most recently "The Tea Girl of Hummingbird Lane." Like those books, "The Island of Sea Women" focuses on women's friendships and family bonds.

The core friendship is that between Young-sook and an orphan named Mi-ja. They're the same age but come from very different backgrounds. Young-sook is the oldest child of a loving family; her strong mother, Sun-sil, heads one of the island's haenyeo collectives.

Mi-ja's mother died giving birth to her; her father dies when she's 7 years old. She's sent to live with an aunt and uncle in Young-sook's village of Hado. They treat Mi-ja so badly that, when Young-sook and her mother meet her, the half-starved girl is stealing food from their fields.

That might seem an inauspicious beginning, but the girls are soon as close as sisters, and Sun-sil sees enough potential in Mi-ja to treat her like another daughter, training both girls to step into the role of "baby-divers" as part of the collective.

In 1938, Hado was an isolated place; when the girls meet, Young-sook has never learned to read, tasted sugar or seen a car, and Mi-ja has to explain to her what electricity is. Mi-ja, on the other hand, lived with her father in Jeju City, the island's metropolis, where she learned to speak Japanese and even read and write a few words.

Jeju Island, off the southern tip of South Korea about midway between China and Japan, has for centuries been a "stepping stone" for a series of invaders. Its natives have long fought to maintain their own culture and language. Young-sook can't remember a time when it wasn't occupied by the Japanese military; Mi-ja's entire life will be shaped by the fact that her father and, later, her husband are collaborators with the Japanese.

World War II, the Korean war and the war in Vietnam will all wash up on Jeju's shores, bringing tragedy to many of See's characters. Young-sook and Mi-ja will travel beyond those shores, living and working in China, Japan and Russia; one of them will wind up in the United States.

But the most intriguing parts of the book are those that describe the lives of the haenyeo. Their job is physically and mentally demanding: They dive into often-icy waters clad only in thin cotton bathing costumes, armed with knives and nets, without any kind of breathing apparatus. After a while, they all speak in loud voices, because the water pressure damages their ears.

The interdependence among members of the collective is a matter of survival. They gather and sell sea creatures that might seem harmless if you've only seen them on a plate. But See reveals how perilous the work can be: One diver is almost killed by an octopus, and another drowns because of an abalone.

Yet the women love the sense of freedom, competence and strength they find in the water. When they're pregnant, they hope to give birth while they're diving (no maternity leave for haenyeo) because they feel the baby will "slip out" more easily.

Bonded tightly on the job, Young-sook and Mi-ja are abruptly separated when they enter arranged marriages within days of each other. One will stay and one will go. As Young-sook says, "We were two brides filled with sorrow, unable to change our fates. I loved her. I would always love her. That was far more important than the men we were to marry. Somehow we would need to find a way to stay connected."

They do keep a connection until a terrible event tears them apart. Many years later, on that beach full of tourists, Young-sook will dive once more into the past, searching this time for the truth.Tampa Bay Times