BOZEMAN, Mont. - It sounds like a fairy tale.

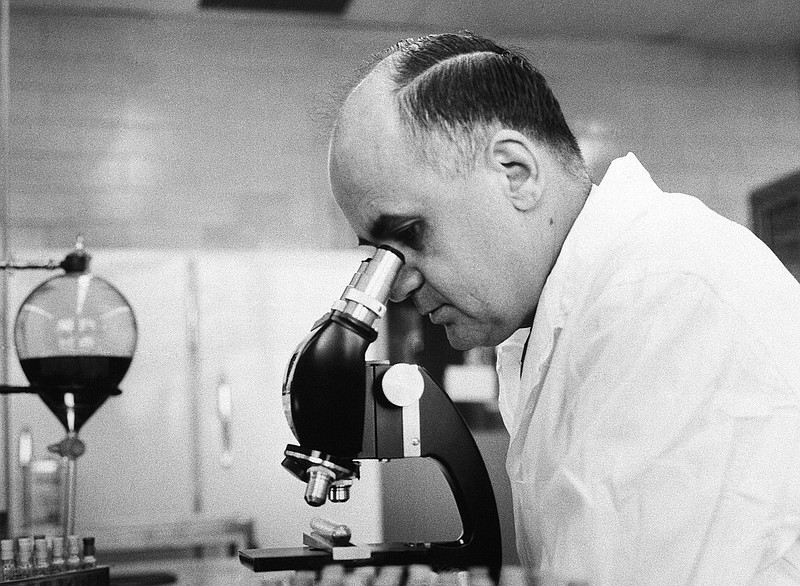

A poor boy, born in tragedy and raised by his aunt and uncle on a Montana farm, would grow up to become one of America's greatest scientists, a wizard at developing vaccines, credited with saving 8 million children's lives around the world each year.

Yet most people don't even know his name.

Maurice Hilleman was born 100 years ago near Miles City on the high plains of eastern Montana. He would grow up to develop vaccines against measles, mumps, chickenpox, pneumonia, influenza, meningitis and hepatitis and other diseases.

Hilleman is credited with saving tens of millions of lives worldwide - more than any other scientist of the 20th century, the New York Times reported in 2005 when he died at age 85.

Ninety-five percent of American children today receive the MMR vaccine against measles, mumps and rubella that he developed. The vaccine has made those miserable childhood diseases - which caused rashes, fevers and swelling in most kids, but also caused some serious disabilities, deafness, birth defects and even death - seem like ancient history to many families.

"He couldn't stand to see children suffer," his widow, Lorraine Hilleman, 86, told the Bozeman Daily Chronicle during a recent visit from Palo Alto, California, to Bozeman. "He couldn't stand to see adults suffer, either."

"I think what drove him was this obsession to prevent every childhood disease," said daughter Kirsten Hilleman, 54, a New York resident moving to Big Sky. Once he'd figured out one vaccine, he would tackle the next disease.

Thanks to Hilleman's vaccines, wrote biographer Paul Offit, today we live an average of 30 years longer than a century ago.

Maurice invented vaccines based on the ideas of Louis Pasteur and other early scientists. The idea was to take a virus and weaken it - often by passing the virus through cells from chicken embryos - until it was too weak to cause the full-blown disease, but still potent enough to spark people's immune systems to produce their own natural antibody defenses to fight off the disease.

In 1948 he started work for the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Washington, D.C., and did key research on influenza. He discovered the influenza virus would mutate in small ways each year, called drift. And sometimes the virus would mutate dramatically, called shift. That could create deadly pandemics because people had no immunity against the changed virus.

In 1957 he read a New York Times story about a widespread influenza outbreak in Hong Kong, and had a gut feeling it could be the next pandemic. At the Army lab he confirmed it was the same strain that caused a pandemic 67 years before, and against it only a few elderly people had immunity. He worked 14-hour days to develop a vaccine before the virus reached the United States, and 40 million doses were created to protect the American public.

Some 70,000 people died, but health officials said it could have been a million without the vaccine. The military awarded him the Distinguished Service Medal.

Maurice was then recruited by the Merck pharmaceutical company in Pennsylvania, where he would lead virus and vaccine research for 45 years, developing most of the 40 vaccines for which he and his team were credited.

A key year was 1963, when he was working to improve a measles vaccine, eliminating bad side effects of rashes and fevers. Measles then killed about 500 American children each year.

One night his 5-year-old daughter Jeryl Lynn then came down with the mumps. In most children mumps caused a painful swelling of the glands in the neck, but it could cause more serious effects. He swabbed her throat to collect the virus that became the basis of today's mumps vaccine.

By 1971 he was able to combine vaccines against measles, mumps and rubella to create today's MMR vaccine. Instead of having to come in for a series of six shots, now children needed just two.

"MMR was one of his big breakthroughs, and hepatitis B," Lorraine said. The hepatitis B vaccine was the first against a virus that causes cancer in people. "I consider those his two big breakthroughs."

Other vaccine scientists became famous - Pasteur for the rabies vaccine, Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin for polio vaccines. But Maurice Hilleman never put his name on his inventions.

"He had no ego," Kirsten said. "He was humble, modest."

Maurice was always generous, sharing the credit with his whole team, Lorraine said.