BALTIMORE-The patient was dead, but the cause remained a mystery. And if there's anything doctors hate more than their inability to forestall death, it's their inability to explain it.

And so, 357 years after Oliver Cromwell died at age 58, several dozen physicians convened here under the austere arches of Westminster Church this fall to ponder the patient's medical history, assess his symptoms in his final days, and settle upon a cause of the English statesman's death.

There would be no physical examination of the man who, in the 17th century, dethroned an English king, brutally suppressed Catholic uprisings in Ireland and united an empire riven by dissension.

A diagnosis would have to proceed without the niceties of modern medicine as well: no blood tests, no X-rays or CT scans, not even a proper autopsy (though Cromwell's embalmer observed that his brain's blood vessels seemed to be "overcharged" and that his spleen, "though sound to the Eye," had a build-up of oily sludge that doctors today associate with sepsis).

Most of the time, the unfortunates discussed in such "clinicopathological conferences" died just weeks or months earlier. A staple of medical education, these exercises help doctors and medical students hone their skills and learn from what went wrong (or right) in a patient's care.

But for a growing subculture of physicians across the country, piecing together a historical figure's cause of death is a puzzle that combines their diagnostic skill and medical intuition with biographical research, archival excavation, epidemiological sleuthing and a dash of guesswork.

"It is the ultimate whodunit," said Dr. Sanjay Saint, who, after weeks of research and deliberation, concluded that Cromwell had died of malaria-which was endemic to the British Isles at the time-combined with a salmonella infection that gave him typhoid fever.

"The reason we go into medicine is to help patients," said Saint, the associate chief of medicine at the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System in Ann Arbor, Mich. But that's not all.

"There's also that part of playing detective, of being curious about a mystery and wanting to figure it out."

Dr. Jan Hirschmann, a staff physician at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle, caught the medical detective bug nearly 20 years ago, and has been at it off and on ever since.

On a lark in the late 1990s, a musician and medical colleague of Hirschmann's invited him to lecture on the untimely death of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in 1791, just shy of his 36th birthday. Hirschmann, an infectious disease expert and insatiable reader with a penchant for problem-solving, knew next to nothing about Mozart's life or the circumstances of his demise. But the challenge sounded like fun, and he soon dove into every biography he could find.

Mozart had suffered from a fever with joint pain as a child, which some doctors have interpreted as acute rheumatic fever. Because this can lead to chronic heart complications, many assumed the Austrian composer died of heart failure.

One music historian suggested Mozart had been poisoned by his archrival, Italian composer Antonio Salieri. Other candidates for cause of death included kidney failure and infective endocarditis.

None of those diagnoses added up, Hirschmann thought. Mozart's family letters said he was "in perfect health" before he was suddenly overtaken by fever and a skin rash.

These symptoms-along with physicians' notes and diary entries from the time-pointed to some sort of outbreak. The only one that matched Mozart's symptoms was trichinosis, a parasitic disease caused by eating undercooked meat, usually pork. But Hirschmann had one big problem: He didn't know what Mozart ate.

As he sat in the hospital library waiting to give his lecture, he leafed through a book one last time. That's when he came across a letter that stopped him cold.

Mozart was writing to his wife, Constanze, when he was interrupted by a servant bringing dinner. He wrote:

"And what do I smell? Pork cutlets! Che gusto. I eat to your health."

The letter was dated Oct. 7, 1791. Mozart fell sick 44 days later-the time it typically takes for trichinosis symptoms to appear after infection.

Triumphant, Hirschmann presented his findings to a fascinated audience. He published them in the Archives of Internal Medicine in 2001.

"I call it the smoking-or not-so-smoking-pork chop," he said.

The diagnosis produced what Hirschmann laughingly calls the two "acmes" of his career: a spot in the grocery store tabloid the Star and a mention in Jay Leno's "Tonight Show" monologue.

"That got me my 15 minutes of fame," he said.

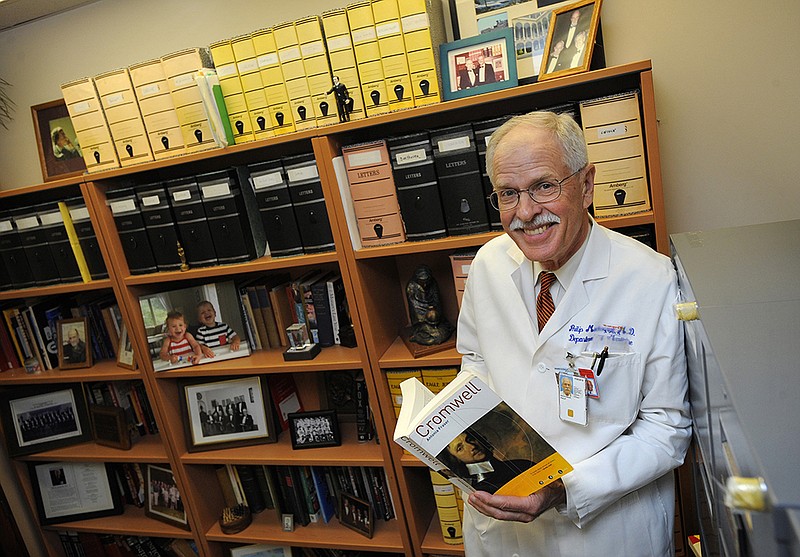

It also got him noticed by Dr. Philip A. Mackowiak, the University of Maryland physician and epidemiologist who launched the medical school's annual Historical Clinicopathological Conference back in 1995.

Mackowiak asked Hirschmann to investigate the death of Herod the Great in 4 B.C., when the Judean ruler was 69. (Hirschmann's diagnosis: kidney disease, complicated by Fournier's gangrene.)

Over the last 20 years, Mackowiak's medical sleuthing has reached as far back in history as ancient Greece (the statesman Pericles probably succumbed to typhus fever in what was called "the plague of Athens") and as close to home as Baltimore (the writer Edgar Allan Poe most likely died of rabies).

To solve the riddle of Cromwell's death, Mackowiak this year invited a new kind of sleuth to weigh in. While Saint hit his books, computer specialists from the U.S. Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee fed details of Cromwell's medical history into a network of supercomputers. A software program designed by Oak Ridge engineers churned through 27 million medical articles and texts, analyzing 70 million data associations relevant to Cromwell's case.

In 4.5 seconds, ORIGAMI-short for Oak Ridge Graph Analytics for Medical Innovation-converged on virtually the same conclusion drawn after weeks of research and deliberation by Saint: Cromwell was done in by malaria.

For Saint, the unexpected competition was a humbling reminder of his limitations.

But for Dr. Eliot Siegel, a University of Maryland radiologist and nuclear medicine specialist who worked on the ORIGAMI project, the exercise underscored the astonishingly efficient brainpower physicians bring to the task of diagnosis. Years of education and practice have endowed physicians such as Saint with a trove of medical data and an arsenal of cognitive shortcuts.

"Who would I rather have making a diagnosis? It would be hands-down Dr. Saint," Siegel said.

On the other hand, "if you told me there was a mystery disease and no one had any ideas about it and we needed some new insight I like the computer."

Oak Ridge engineers are preparing to reopen several of the cases pondered by Mackowiak and his colleagues through the years. The results may upend some of the conclusions so painstakingly drawn-and deepen the medical mysteries thought to

be solved.