WASHINGTON-Profound differences between House and Senate Republicans may play as big a role as GOP fights with Democrats on how the legislative agenda plays out when Congress returns in January.

House Republicans, especially conservative members, have been energized by their ability to rally around the tax overhaul and to limit demands from Democrats-and from the Senate-on the stopgap spending measure that closed out the year and will keep the federal government running through Jan. 19.

With the tax plan now law, House Speaker Paul Ryan has set his sights on another long-held Republican goal: reforming safety-net standbys such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, popularly known as welfare and food stamps, and used by millions of poor, disabled and elderly Americans. Ryan also spoke, on Dec. 6., of overhauling Medicare, calling it the "biggest entitlement."

But then there's the Senate, where Republicans will have the slimmest possible margin in 2018 and the chamber's rules give minority Democrats significant leverage to bottle up proceedings. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, recognizing that reality, shot down the idea of attempting to jam through Republican-only legislation.

"There's not much you can do on a partisan basis in the Senate with 52-48 or at 51-49, which would be the number of us for next year," McConnell said at a news conference on Dec. 22. "I don't think most of our Democratic colleagues want to do nothing, and there are areas where I think we can get bipartisan agreement."

Republicans will hash out these differences at a retreat in January, after which they're expected to announce their legislative agenda for the months running up to the 2018 midterm elections in November. Before that, McConnell and Ryan will meet with President Donald Trump at Camp David to line up priorities.

McConnell says his agenda for early 2018 will be dominated by a drive to forge a broad agreement on agency spending for the rest of the fiscal year; a bipartisan measure loosening Dodd-Frank banking rules for smaller institutions; and an immigration overhaul if negotiations between Republicans and Democrats can reach an agreement.

He's all but rejected the idea of another attempt to repeal Obamacare or taking on reform of welfare programs or so-called entitlement programs like Medicare. McConnell said such attempts can only be successful when both parties agree on the terms-for example, as in the case of changes to Social Security made under President Ronald Reagan.

"The only way I would be willing to go to entitlement reform-I assume that's a euphemism for things like Social Security and Medicare-would be if there were Democratic support," McConnell told the Wall Street Journal.

This suggests McConnell recognizes how hard it would be to get 51 Senators to agree on changes to programs, like food stamps, that help individuals and families facing hardship-let alone on Social Security, which pays benefits to tens of millions of retired workers and their dependents, as well as to millions more disabled workers and others.

That means Republicans could need help from Democrats even on bills moving through the budget reconciliation process to fast-track passage with only a simple majority. More contentious measures would be likely to face Democratic filibusters.

Ryan, on the other hand, and many of his House Republicans, see overhauling social programs as the essential next step after their rewrite of the U.S. tax code, which is forecast to drain some $1.5 trillion from federal tax revenues over the next decade. Ryan contends that reforming entitlement programs and increasing economic growth by lowering taxes are both necessary to pay off the federal debt.

"We will get back at reforming these entitlements," Ryan told Fox News's Martha MacCallum last week. "We're going to take on welfare reform, which is another big entitlement program, where we're basically paying people-able-bodied people-not to work."

As a candidate, Trump promised repeatedly that he wouldn't cut Medicare, the provides health insurance for older Americans, or Social Security. Other safety-net programs may be fair game, though. The president said in November that "we're looking very strongly at welfare reform, and that'll all take place right after taxes." And Ryan has said that Republicans are making an impression on Trump when it comes to Medicare reform.

Mandatory spending-that is, funds not appropriated by Congress-on programs like Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid represents more than half of U.S. government outlays.

In the House, Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi has made it clear she doesn't plan to help Republicans hunt for savings in those areas. Pelosi pushed back hard on the Republican fiscal argument of using the revenue lost to their massive tax cuts as an excuse to shrink the size of government.

"This is part of the 'starve the beast' value system that the Republicans have," Pelosi said on Dec. 21. "They do not believe in governance, so any public role in the health and well-being of the American people is on their hit list."

The ideological divisions are even more complicated when it comes to immigration, one of the first issues Congress has to tackle when it returns in the new year.

McConnell said on Dec. 20 that he'd commit to putting on the floor in January legislation combining deportation protections for 800,000 young undocumented immigrants with a border security package. That's contingent, though, on bipartisan negotiations yielding a deal "that can be widely supported by both political parties and actually become law."

Ryan hasn't committed to this timetable. He leads a chamber where conservatives will balk at the deportation protections if they include a pathway to citizenship for the so-called "Dreamer" immigrants, which appears likely in the Senate. Some House Republicans also seek more conservative immigration law changes than any Senate deal is likely to embrace.

Although Ryan has said he wants to provide some kind of legal certainty for immigrants who were protected under Obama's Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, he's played down any sense of urgency-saying he needs to find out where his own conference is on this issue before he can negotiate with the other side. Trump has extended the protections into the early spring.

"Do we have to have a DACA resolution? Yes, we do," Ryan told reporters in November. "The deadline's March, as far as I understand it. We've got other deadlines in front of that, like fiscal year deadlines and appropriation deadlines."

Even though Pelosi backed down from an earlier pledge to force the issue before the end of 2017, she said the six-month deadline set by Trump's DACA decision in September leaves at-risk people with too much uncertainty.

"They're saying, well, we can wait until March. Well, we can't," Pelosi said. "And as I said to them, that's an act of cruelty to say you can wait until March when people are losing their status every day."

Congress' last significant action on immigration was in 2013, when the Senate-then controlled by Democrats-voted to create a path to legal status for 11 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S., and to spend $46 billion to secure the U.S.-Mexican border. The Republican-dominated House didn't take up the bill, as most in the party opposed legal status.

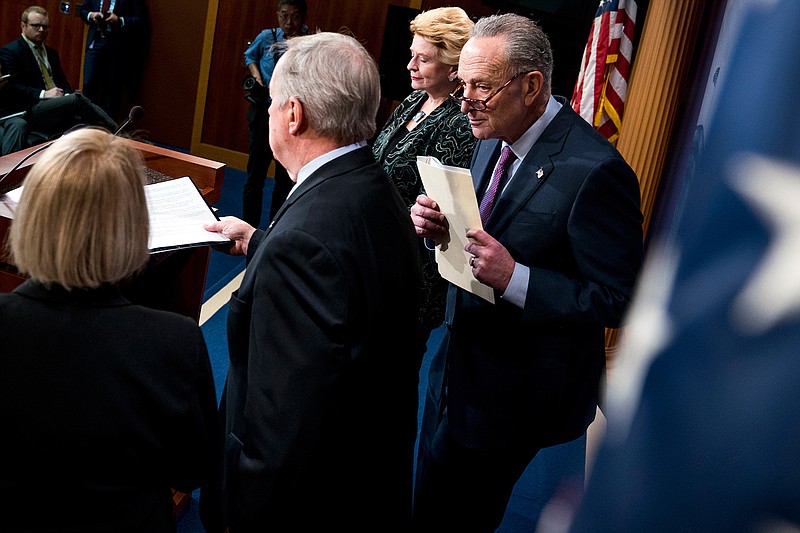

In the immigration debate, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer is urging McConnell to put a deal on broad legislation into the next spending bill, expected to be considered by Congress in late January to keep the government running.