Jackie Robinson broke baseball's color barrier in 1947, but it wasn't until three seasons after Robinson last played that Major League Baseball became fully integrated.

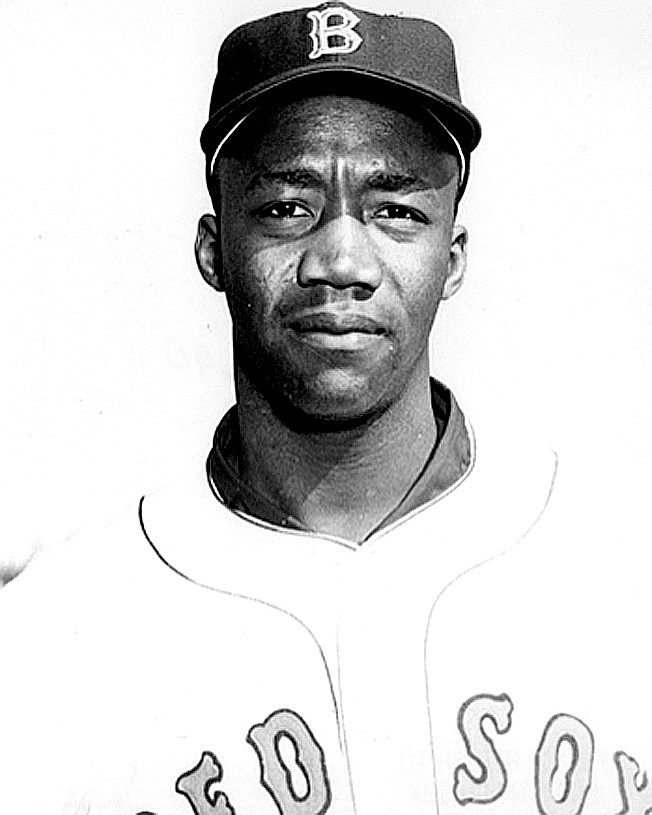

That happened on July 21, 1959, when Pumpsie Green made his debut for the Boston Red Sox, the last MLB team to employ a black player.

Green, 83, has lived his life in reluctant acceptance of his place in history. He did not intend to be at the end of the path that Robinson blazed.

"My dad is a quiet man, he's very introspective," said Keisha Green Joyner, Green's daughter. "So I can see why he wouldn't want that kind of attention. He just wanted to play baseball."

Pumpsie Green-his given name is Elijah-lives in El Cerrito, Calif. He never publicly disclosed the origin of his nickname, only that his mother started calling him that at a young age. Even his daughter says she doesn't know the origin. It's "still a mystery," she said.

An infielder, he played four seasons for the Red Sox and 17 games for the 1963 Mets. Green Joyner said her father is in ill health and unable to give interviews.

Green was born in the historically black town of Boley, Okla., and grew up in Richmond, Calif.

He came from an athletic family. His brother Cornell was a five-time Pro Bowl performer in a 13-year career with the Dallas Cowboys. His brother Credell starred at Washington State and was drafted by the Green Bay Packers.

Pumpsie, a three-sport star at El Cerrito High School, was 25 when the Red Sox called him up from the Double-A Minneapolis Millers on July 1, 1959. Jackie Robinson called to congratulate him.

___

Before Green's arrival, the Red Sox reportedly passed on Robinson and Willie Mays, not to mention Larry Doby, Ernie Banks, Roberto Clemente and Hank Aaron-other future Hall of Famers who were available but signed by other teams.

The Red Sox were owned by Tom Yawkey from 1933 until his death in 1976. His daughter, Julia Gaston, 80, refused to discuss any racial policy that may have been in place during her father's tenure. "Sorry, I can't help," she said from Wilton, Conn.

Corky Cronin, a 75-year-old retired commercial banker in Massachusetts, is familiar with the Red Sox of that era. His father, Joe Cronin, managed the team from 1935-47 and became president of the American League before the 1959 season.

"The facts appear to support that assertion" that at one time the organization did not want black players, Corky Cronin said.

Before spring training of 1959, the NAACP pressured the Red Sox to bring a black player to Boston. Green was invited to camp in Scottsdale, Ariz., a segregated city.

"Shut Out: A Story of Race and Baseball in Boston," by Howard Bryant, quotes New York Post columnist Milton Gross' report from Arizona: "From night to morning, the first Negro player to be brought to spring training by the Boston Red Sox ceases to be a member of the team he hopes to make as a shortstop.

"But segregation doesn't just come in buildings such as the Safari hotel in Scottsdale where the Red Sox stay or the Frontier Motel where Red Sox secretary Tom Dowd deposited Boston's first Negro when he arrived at camp ... It comes when a man wakes alone, eats alone, goes to the movies every night alone because there's nothing more for him to do and then in Pumpsie Green's words, 'I get a sandwich and a glass of milk and a book and I read myself to sleep.' "

(EDITORS: BEGIN OPTIONAL TRIM)

After spring training, Green was sent to Minneapolis.

Cronin's son said that during his father's tenure there was concern for how black players would be received. "I do know he had great fear of how a black player would be treated in Louisville, Kentucky where the Red Sox Triple-A farm club was. I know that he was a pragmatist and certainly not a racist."

The Red Sox weren't much of a draw in 1959-their home attendance was 984,102-but those who went to the games were vocal and not necessarily accepting.

Green's teammates, according to infielder Ted Lepcio, had spent spring training more concerned about whom Green might replace rather than about his being the first black player on the team.

"None of us played with a black kid," Lepcio, 87, said from Dedham, Mass. "I already was with the ballclub my eighth year. None of the guys I played with played with a black player. I hate to plead innocence, but none of us experienced what he went through. None of us knew there was a player that was going to be segregated from us, go in another place, not in our hotel.

"We weren't observant enough. Little did we know that some of the black players didn't stay at the same hotel. We were totally oblivious. We were all with the same group, all white players."

(END OPTIONAL TRIM)

___

"Understanding Pumpsie Green is very simple," Bryant said last week from Northampton, Mass. "Here's a guy who had no interest in being where history placed him. It really had nothing to do with him. He suffered in a lot of ways because this was all an accident. It was an accident of bad history. It was an accident of all of the mistakes that were committed by other people.

"The only reason anybody should have remembered Pumpsie Green is because he had a phenomenal nickname. Instead, he was placed into something that was very toxic," Bryant said. "He certainly was not equipped to deal with what went his way. He tried to do what is a very hard thing to do, play baseball at the major-league level, and an even harder thing to do when you're being expected to be some sort of pioneer. It's one thing for Jackie Robinson, a player of Hall of Fame level, for Hank Aaron; quite another when you're a mediocre infielder trying to hang on."

Green did not think his experience was unique, "It was every black, not just me," he told the San Francisco Chronicle in 2009. "So that was the only solace I had. 'It's not just you, Pumpsie, it's all blacks.' "

___

Green always declined to be drawn into the race issue. "So far as I'm concerned, I'm no martyr," he was quoted as saying in 1959. "No flag carrier. I'm just trying to make the ballclub, that's all. I'm not trying to prove anything else but that. I'm not even interested in being known as the first Negro to make the Red Sox. I just want to make the Red Sox and all the rest of it can wait."

In 2000, reflecting on those times, Green told Bryant: "Sometimes when I think of the things people like me had to go through, it just sounds so unnecessary. When you think about it, it's almost silly, how much time and energy was wasted hating."

His 344 games-a .246 batting average with 13 home runs and 74 runs batted in-belied his importance to the sport.

In 1997, Green came back to Fenway Park. "Jackie Robinson's daughter (Sharon) and my dad threw out the first pitch," Green Joyner said. It was symbolic, she said, of "being the first and last" to integrate baseball. "Jackie Robinson was the first, my dad was the official last."

Green Joyner said she is sure her father is proud of being the final person to obliterate segregation in the majors.

"He can look back on his life and say he's done what he wanted to do, and not everybody gets that opportunity to say that," she said. "He internalizes a lot of the things that he's gone through. He's always been a very humble man. But I think that there's a lot of stories in him that we don't know. And we probably would never know.

"He doesn't want people to know some of the horrific things he's seen and had to deal with. So I think he internalizes those things and gets quiet. But, you know, my dad is a fighter."