SIMMS, Texas-As a 24-year-old Army private, William L. Cook felt reasonably safe riding in a U.S. Army transport truck near Metz, France, in October 1944-until a sudden blast changed his mind.

"We were traveling on a road that was supposed to have been mine-swept, but it wasn't," said Cook, 95, as he recalled his days serving an assistant driver of a U.S. tank destroyer stationed with the 3rd Army in Europe during World War II. "We were headed back in a transport truck to get some water when we hit a German land mine and it exploded. I was sitting up front on the passenger side, and I was blown up into the air and out of the truck. I later found myself laying on the ground."

Two other American soldiers happened to be in a nearby jeep. They managed to pick Cook up, load him in the jeep and take him to a medical aid station in a field about half a mile away.

Cook was born July 30, 1920, in Ellis County outside Palmer, Texas. His family worked as tenant farmers in cotton fields just before the Great Depression started in October 1929.

Cook only made it to second grade in public school before having to quit and pick cotton at age 8. His desire was to be a musician.

"With just a second-grade education, I thought about becoming a barber, but after I took an aptitude test, I found out that I didn't even have enough education to get into barber school," Cook said. "That would have been a six-month program."

Faced with the sudden death of his father in about 1933, Cook, who by that time was 13, and his mother were forced to to move to the city to find work. They journeyed to Dallas, where Cook took a job as a runner, distributing business advertising flyers in residential neighborhoods.

While working as a runner in Dallas' Oak Cliff neighborhood, Cook acquired a guitar and played and sang on street corners for tips until at age 16. He then joined a country and western music band, learned to read music and started performing at Dallas-area night clubs.

"If you were pretty good and people started to like your band, you got to stay at clubs and perform," he said.

But the war interrupted and temporarily changed Cook's career path when he received his draft noticed. He answered the call to military service. After basic training at Camp Walter in Mineral Wells, Texas, he went to California's Mojave Desert for more training with an armored tank destroyer battalion from February to September 1943.

Following, his seven-month stay on the West Coast, the Army sent Cook back to the Lone Star State, where he was outfitted for additional training in armored tank destroyers with 76 mm guns at Camp Maxey near Paris.

"I also spent a lot of time on guard as well as on KP (kitchen patrol)," he said.

By February 1944, Cook was at Camp Myles Standish for six weeks before setting sail to England.

"While in England, we prepared for the Normandy Beach invasion of France, but we wound up going in on June 12th (1944), six days after the initial landings. That's when the Army put us in combat," he said.

Cook and his tank destroyer crew were attached first to the 1st Army and later to Gen. George S. Patton's 3rd Army. One of the first places they captured was an abandoned German field kitchen.

"We found ourselves in a low fog one morning as we searched through a former German mess hall," Cook said. "We came upon some canned bacon, but we didn't have time to cook it until three weeks later, so we boxed it up. Once we cooked it, it smelled so good cooked outside on an open stove," Cook said.

But to Cook and the rest of his outfit, the pleasure was short-lived.

"We started hearing German tanks approaching, so we tried to gather our things and get moving, but then we heard them fire their armor-piercing shells at us, so we didn't even have time to put out the fire on our stove. We just moved on out," he said.

Cook's group was embroiled for the next two or three weeks in the Battle of Saint Lo, as American ground forces targeted the city for capture-mostly because of its strategic crossroads.

"We were told to dig trenches, and we were a couple (of) miles from Saint Lo when we saw hundreds of Allied fighter and bomber planes fly over," Cook said. "I could feel the ground shaking from all the bomb explosions, and the wind blew the smoke back over us. Saint Lo was so well-secured by the Germans because they had big guns mounted on elevators that could bring them up from underground storage. It seemed like it took every plane just to knock out those guns."

The French country side's generous hedgerow acreage also presented as much cover for the enemy as it did for the Allies. But Cook's unit proceeded steadily across northern France after Allied ground armies forced a general German retreat, following the enemy's near encirclement in the Falaise pocket, just south of the Normandy, by mid-August 1944. The Allied maneuver resulted in the capture of a few thousand German prisoners of war.

"We didn't have time to dig trenches, so we just climbed into bomb craters and shell holes to take cover as the Germans fired at us from the woods," Cook said. "I was told to guard some of the German POWs, so I took my M-1 and fired it into the air. Then I told the Germans to get in line, and they did. They were given some room to run along the roadside next to our tank destroyer."

Cook, the assistant driver for his crew's tank destroyer, also got some reconnaissance assignments as his crew became attached to the 3rd Army-a unit that was approaching the French-German border.

"The Army started sending us on reconnaissance missions to places near Germany," Cook said. "We actually had German riflemen firing on us at one point.

"One time they even managed to knock out tank destroyer with mortar shells. We had another tank destroyer that was operable, and it had a jeep attached to the back of it, but the Germans were still shelling the area pretty good. I ran and tried to take cover in a large drainage pipe in a ditch near the side of the road, but since the Germans were still shelling us, my crew tried to get our new tank destroyer, out of the way of shell fire. I turned away from the drainage pipe and started running after the jeep. That's when our driver stopped, and one of our men in the jeep stuck out his hand and pulled me inside while enemy shells were falling all around. I was happy to be a passenger, and we got out of that area and back to where it was more peaceful."

Cook and his outfit also had to take cover in a French vineyard before making a quiet withdrawal.

"The Germans had put a mounted machine gun nest close to where our tank destroyer was," Cook said. "We initially stopped when we saw it, then we started out for that nest (on foot). That's when our crew sergeant stopped us and told us to stay below the top of the grape vines."

At this point in the war, October 1944, the Allied high command was shifting fuel, food, ammunition and other supplies away from the 3rd Army to bolster British efforts at advancing in Holland. It was during this stalled time that a transport truck Cook was riding in tripped the enemy land mine.

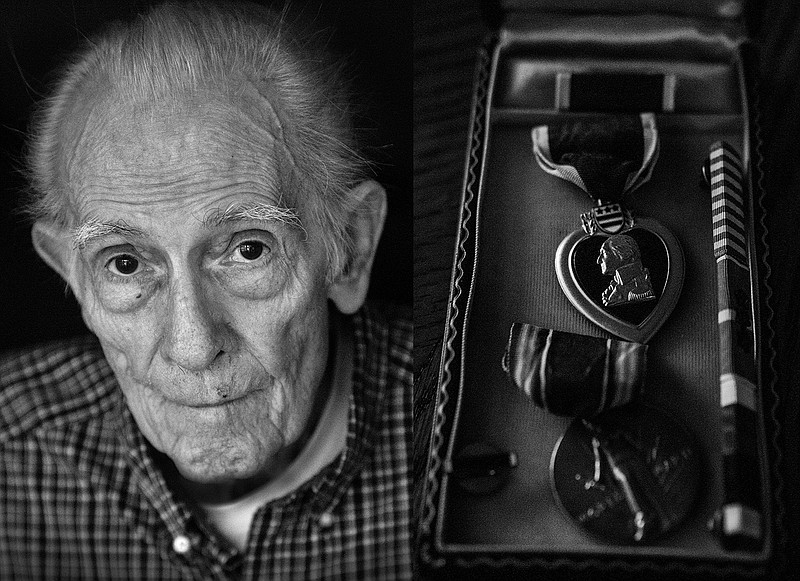

"I suffered an injury to my right knee and left ankle," Cook said. "I had to be taken to two or three separate field aid stations for treatment. I eventually would up in a hospital in Paris for bout six weeks. They put two casts on me (one on each leg).

By Christmas of 1944, Cook had to be flown back to England for recovery.

"While I was recovering from my wounds, the doctors tried to decide whether or not I should go back to the states or stay there in England," Cook said. "They sent me to first to a rehab hospital and eventually decided to send me back home on a hospital ship to Boston."

In Boston, medical authorities decided to send Cook to Tacoma, Wash., for additional recovery.

"There in Washington state, I was finally able to get the casts off, and I started using walking crutches for about a month," he said. "Then I was able to gradually walk again."

Once Cook regained his ability to walk, the Army sent him to San Antonio for more rehabilitation around May 8, 1945. That's where he heard that the war in Europe had finally ended.

"I was glad to hear that the war was finally over, but at the same time, I felt depressed about having to leave my outfit before it all ended," said Cook, who received his discharge in Tyler, Texas."I hitched back to Dallas from Tyler, because I didn't want to stick around. I wanted to get back home. We all came out of the Great Depression to work together, to win this war. Today, I don't think it's necessary to get overly friendly with other countries. We need to show some strength."