AUSTIN, Texas-As solutions to long-standing national problems go, a spit sample might seem a little underwhelming. And yet University of Texas officials say a spit sample, and the way it was collected, offers lessons for dealing with a problem that has vexed American universities for decades.

The sample belongs to Adriana Quintanilla, a UT freshman considering a career in the medical field. Quintanilla collected it as part of a program that is developing various kinds of devices with which people can check for diseases, such as the Zika virus.

This is a rare thing for a freshman. Quintanilla's first experience with science was not, as education consultant David Goldberg calls it, the "the math-science death march": the thick textbooks, abstract concepts and boring labs that usually precede meaningful hands-on work. Experts say early hands-on work early could be the difference between students such as Quintanilla sticking with science tracks or abandoning them.

"I didn't think I would enjoy it, but I do," Quintanilla said. "I'm learning about the kind of research I didn't know we could do."

UT officials say the university's Freshman Research Initiative, which is a decade old, is now a proven approach to a national challenge. As far back as the 1980s, groups such as the National Science Board were warning the nation's universities that they were driving as much as 60 percent of budding scientists, technological innovators, engineers and mathematicians into other fields. This in turn created a dearth in important and well-paying industries.

The United States higher education system now needs to produce an additional 1 million students with degrees in STEM fields over the next decade to meet basic demand, according to a report from a panel of academics and industry leaders convened by President Barack Obama, who made that goal official U.S. policy.

Other universities are now copying UT's approach. Meanwhile, the UT program is wrestling with financial pressures felt across higher education and the question of whether, in an era of cutbacks, the university should expand it to any interested student-a goal that would require a major infusion of funding. As they make their pitch, program officials point to a recent study concluding that enrollment in the program raises the odds of a student graduating with a STEM degree by a third.

"UT has accomplished something remarkable," said James Gates, a lead author of the national report. "The university has created an approach to solving one of our nation's most difficult problems."

Tim Riedel, now a UT professor, doesn't use the term "math-science death march." But he describes his experience at UT navigating the traditional undergraduate training in similar terms.

He was bored. He was impatient with simulating science, rather than doing it. He looked without success for community among students in the echoing lecture halls where tiny figures gave distant lessons basic enough to apply to numerous fields.

"I was miserable," Riedel said. "I was really frustrated. I changed majors four times."

Can a lightly trained 18-year-old be trusted to accomplish meaningful science?

Riedel said a traditional lab setting might be useful in teaching the basics. But he said traditional labs also have pernicious qualities that work against scientific principles. Many of those classes grade students relative to one another, thus encouraging students to compete against one another, rather than collaborate, as scientists almost always do.

Riedel eventually did earn undergraduate degrees from UT, in physics and astronomy, and then a doctorate from the University of Southern California. But he said his career is due in no small part to luck: He was about to quit after knocking on 20-odd doors looking for actual research opportunities when a last-ditch attempt persuaded professor Andy Ellington to take him on. Fifteen years later, Riedel works for Ellington, overseeing more than 40 students in the Freshman Research Initiative in an unusual setup under which his mentorship role is given greater emphasis.

Ellington chuckles when he considers the origins of the Freshman Research Initiative.

It wasn't so high-minded as some might think, Ellington said. He and several colleagues wanted a few more good minds in the labs they ran. Maybe getting a new program off the ground, Ellington reasoned, would give him first dibs.

"I want the best of the best. I want them to be researchers," said Ellington, whose lab conducts research into drugs and technology. "This was a way for some of us to have a very polite cage match for those students."

They started with 15 students. The next year, the program had already grown to 45.

Want to see if you can make a drug that helps with Alzheimer's? A professor (such as Riedel) shows a few students the basics of how to work in a lab, then lets them go at it. Usually, their experiments fail. Even so, the students receive training that makes them more appealing to people running the labs that are the key to unlocking careers in science.

"The thing that I think is worth emphasizing (with such programs) is that failing is OK," Ellington said.

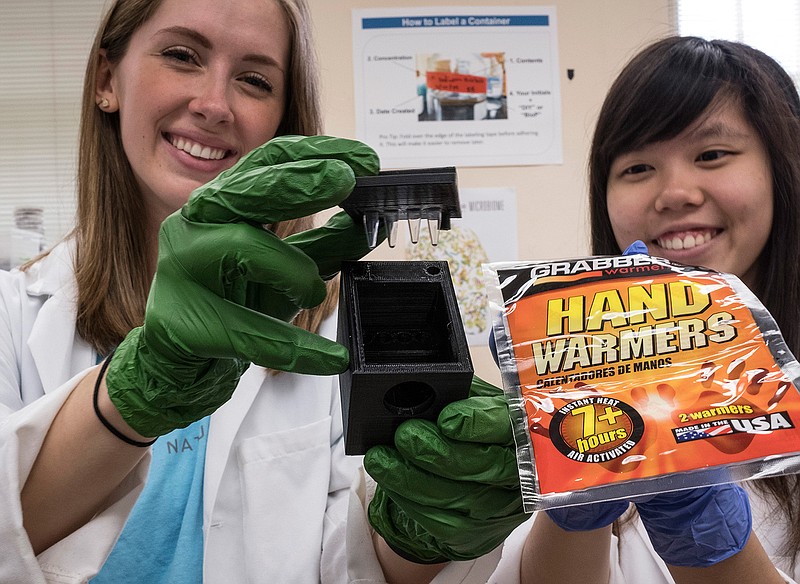

Rachel Boaz, a neuroscience major, and Szu Yu Liu, a nutrition major, heard about the program during freshman orientation. They just finished their sophomore year, surpassing the point where the demands of a STEM degree tend to become apparent and attrition skyrockets.

They work in Ellington's lab as part of the research initiative's DIY Diagnostics "stream." The lab is now working on a way to detect Zika virus. The idea is that, when finished, the lab will have modified pregnancy testers to allow people to test mosquitoes (or their own blood) for Zika.