Colin Carlson, a biologist at Georgetown University, has started to worry about mousepox.

The virus, discovered in 1930, spreads among mice, killing them with ruthless efficiency. But scientists have never considered it a potential threat to humans. Now Carlson, his colleagues and their computers aren't so sure.

Using a technique known as machine learning, the researchers have spent the past few years programming computers to teach themselves about viruses that can infect human cells. The computers have combed through vast amounts of information about the biology and ecology of the animal hosts of those viruses, as well as the genomes and other features of the viruses themselves. Over time, the computers came to recognize certain factors that would predict whether a virus has the potential to spill over into humans.

Once the computers proved their mettle on viruses that scientists had already studied intensely, Carlson and his colleagues deployed them on the unknown, ultimately producing a short list of animal viruses with the potential to jump the species barrier and cause human outbreaks.

In the latest runs, the algorithms unexpectedly put the mousepox virus in the top ranks of risky pathogens.

"Every time we run this model, it comes up super high," Carlson said.

Puzzled, Carlson and his colleagues rooted around in the scientific literature. They came across documentation of a long-forgotten outbreak in 1987 in rural China. Schoolchildren came down with an infection that caused sore throats and inflammation in their hands and feet.

Years later, a team of scientists ran tests on throat swabs that had been collected during the outbreak and put into storage. These samples, as the group reported in 2012, contained mousepox DNA. But their study garnered little notice, and a decade later mousepox is still not considered a threat to humans.

If the computer programmed by Carlson and his colleagues is right, the virus deserves a new look.

"It's just crazy that this was lost in the vast pile of stuff that public health has to sift through," he said. "This actually changes the way that we think about this virus."

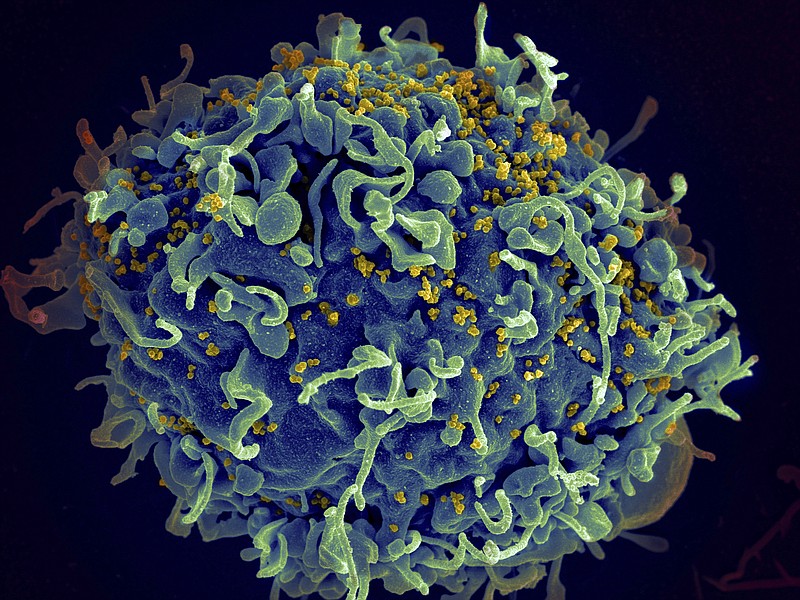

Scientists have identified about 250 human diseases that arose when an animal virus jumped the species barrier. HIV jumped from chimpanzees, for example, and the new coronavirus originated in bats.

Ideally, scientists would like to recognize the next spillover virus before it has started infecting people. But there are far too many animal viruses for virus experts to study. Scientists have identified more than 1,000 viruses in mammals, but that is most likely a tiny fraction of the true number. Some researchers suspect that mammals carry tens of thousands of viruses, while others put the number in the hundreds of thousands.

To identify potential new spillovers, researchers like Carlson are using computers to spot hidden patterns in scientific data. The machines can zero in on viruses that may be particularly likely to give rise to a human disease, for example, and can also predict which animals are most likely to harbor dangerous viruses we don't know about yet.

"It feels like you have a new set of eyes," said Barbara Han, a disease ecologist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, New York, who collaborates with Carlson. "You just can't see in as many dimensions as the model can."

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.