In Maggie Nelson's "Bluets," her 2009 collection of poems on grief and loss, loneliness is "solitude with a problem." Which is a useful way of understanding loneliness. Being alone and feeling lonely are not always the same thing. Except, of course, it's complicated. Emily Dickinson wondered: Was loneliness "the maker of the soul"? Or its "seal"? Does loneliness define you? Or exacerbate what's already broken? Or does it even matter? As Arthur C. Clarke wrote: "We are either alone in the universe or we are not. Both are equally terrifying." Some of us seemed stitched together by our loneliness. Henry Kissinger once said that "the essence" of Richard Nixon was probably loneliness.

OK, now forget all of that.

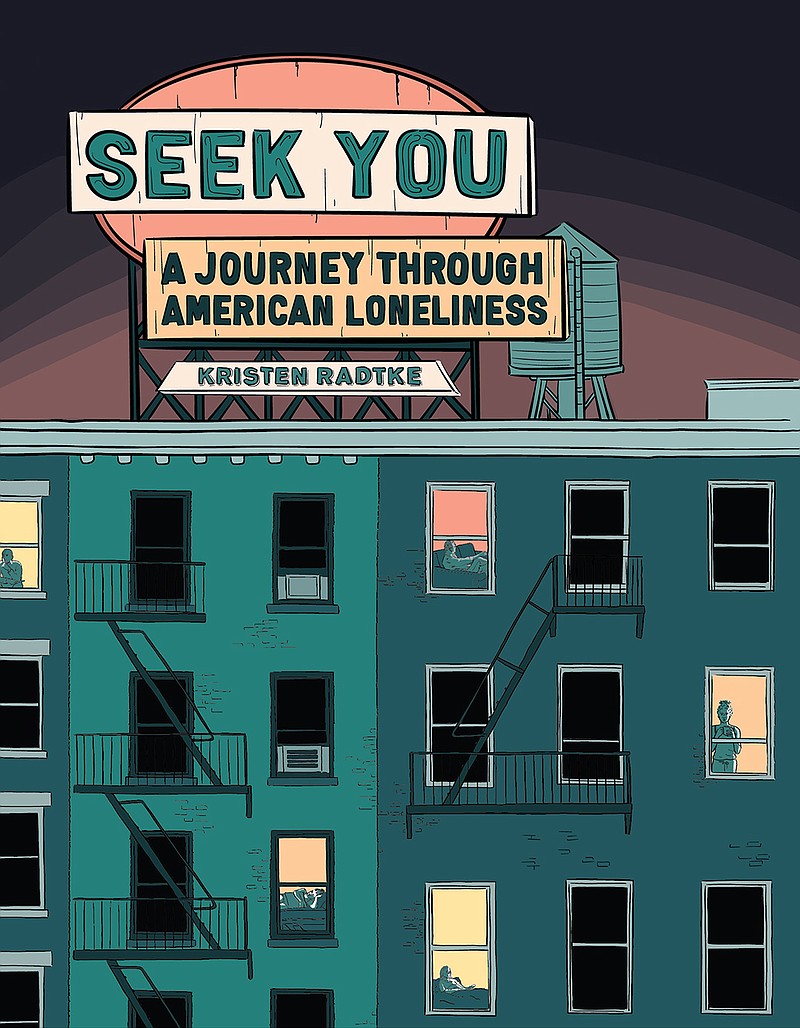

Because Kristen Radtke has written and drawn an excellent new book - a graphic essay of sorts - that's expansive in its approach to loneliness. To her, loneliness is a malady and sometimes a balm, sometimes a diagnosis and sometimes a lens for understanding the United States. Loneliness is among the harshest forms of punishment. Or just a misplaced sense of being out of the loop. When Radtke finally offers the clinical definition - that gap between relationships you have and relationships you want - it feels small.

Not nearly existential enough.

"Seek You: A Journey Through American Loneliness," the author's third book, reads like a kind of sequel to her acclaimed previous graphic essay, 2017's "Imagine Wanting Only This." That book considered our everyday ruins - starting with the crumbling landscape of Gary, Indiana, but then found room for Iceland and Italy, for family tragedy and art and an abiding sense of fatalism. One more book this melancholy, she'll have a High Lonesome trilogy.

Do you have abandonment issues, I asked her.

"Who doesn't?" she said.

Still, the fear of abandonment in "Seek You" - which takes its title from "CQ," or ham radio shorthand for "anyone out there" - seems so acute, when Radtke notes how loneliness is often conveyed glibly by pop culture (a heroine eating at the sink, or owning cats), the harmless becomes cruel.

A few years ago, when Radtke was on her book tour for "Imagine Wanting Only This," she was speaking at a book festival in Wisconsin. It was her hometown and not many had turned out. The auditorium looked sparse. Then someone asked about her next book.

"I said 'loneliness' and it became like a AA meeting. People would raise their hand and we started going around the room and telling stories about the time we felt the loneliest in life. Someone said they called drive-time radio shows just to talk to someone. Right there, I thought, 'Oh, I'm on to something,' this universal feeling we'd prefer to ignore.'"

Indeed whenever she would randomly ask people to tell her about their loneliest moments, the floodgates open and the stories piled up. One part of the book is drawings of some of these people, their stories paired with word balloons beside them.

"That became such a surprise," Radtke said. "I had thought loneliness was not something we admit to, but people leaned in and gave stories with the kind of detail we tend to associate with traumas. These (moments of loneliness) were often after someone gave birth, or were pregnant, or came out, or were newly sober - moments, in our imagination, we expect to feel the most connected. But you're rebuilding yourself."

I told her about the time I moved to London without an apartment and sat in a hotel room for a few nights telling myself if I had a huge mistake - I had screwed up bad.

"Which is why we don't talk about loneliness," she said. "It feels like a personal failing."

Radtke, 34, is art director and deputy publisher of The Believer, the longtime literary journal from McSweeney's. She arrived at her illustrated style of essay while studying for her MFA in the University of Iowa's writing program - she decided that some of what she had to say made more sense as a collage of images or a brief anecdote inside a word balloon.

Radtke grew up near Green Bay, Wisconsin. She said that, from time to time, she has a predilection toward loneliness, but nothing outsized. "Everyone where I grew up lived far away, as in any rural community. My parents were strict, my father was stoic and worked a lot. I had younger brothers. But that's the thing: You can have a strong family and feel lonely."

Americans, it appears, have been headed toward widespread loneliness for a while.

We even have a name for this: the "Bowling Alone" phenomenon - famously identified by Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam, who studied America's decades-long drift away from civic organizations, church groups, neighborhood block groups, bowling leagues. As much as it is possible in an interconnected digital age, we're becoming islands onto ourselves.

Americans, in particular, seem to unwittingly nurturer alienation through our national myths. Rugged individualism, independence above all, an up-by-your-bootstraps ethos, even Batman - it's all rooted in an implicit understanding of a lonely road ahead.

"It's one of the reasons America is such a lonely country," she said. "Trust and loneliness are hugely connected. Without trust, we don't feel connected to one another. So when we go through periods like now, when we don't know what's true, a feeling of isolation creeps in. If you can't be honest with those supposed to be your community, it's alienating, destructive - a lot of problems just expand and fissure outward from there."

You start to see the loneliness at work in the overwork, paranoia, financial anxiety, gun violence. You start to see how retaining some constant degree of loneliness is part of being human, and you feel less alone. Radtke told me she's more actively engaged with her neighborhood than when she began "Seek You." She knows everyone who lives on her block. She says this like it's an accomplishment. Because, in 2021, in the United States, it is.