Many know the power U.S. Congressman Wright Patman wielded in both Texas and Washington, but few are aware of a key conflict early in his career that helped propel him into national politics.

In the early 1920s, the U.S. government required cattle owners in the south to dip their cattle in dipping vats to prevent the spread of Texas tick fever, also known as redwater fever, as it made the cattle urine turn red before the animals died.

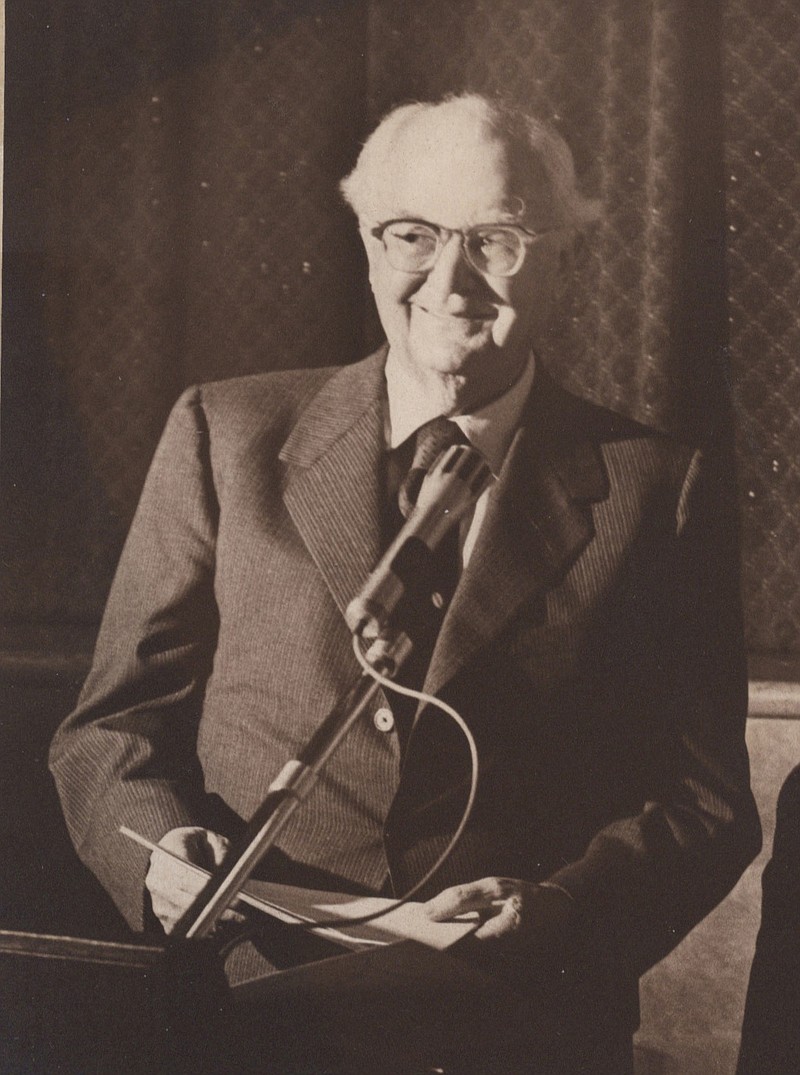

The story, as related by Cass County historian and genealogist George Frost during Tuesday's meeting of Friends United for a Safe Environment, also involves the anti-government Ku Klux Klan in Cass County, which blew up the vats in 1921 and 1922.

"This is a story of how alleviating one problem may create another," Frost said. "Dipping was good, but it was a double-edged sword."

The U.S. put a quarantine on cattle in 1906, he told the group, adding that they could not be shipped north before March 15 due to the rampant spread of the disease.

"They could only ship if the cattle were being slaughtered and couldn't bring in high-class bulls to enhance their herds because they would die of tick fever," he said.

By 1920, ranchers in Cass County and Shelby County were given cement and materials to build the dipping vats and were required to dip the cattle every two weeks in a toxic mixture of creosote and arsenic, Frost said.

"If you didn't do that, you were fined by the justice of the peace and were then forced to dip," he said.

The night before the dipping was to start on March 15, 1921, Frost said 13 or 14 dipping vats in Cass County were blown up simultaneously. Texas Gov. Pat Morris Neff then sent in six Texas Rangers to battle the situation. Frost said the district attorney was not bringing charges against those responsible, who were believed to be members of the KKK.

The vats were rebuilt at the owner's expense and the dipping continued, Frost said, but the ranchers were told, "Do not be around a dipping vat after sundown for your own safety."

A year later, even more vats were blown up and 30 Texas Rangers were sent to Cass County, mostly undercover, to once again address the situation.

"It was basically the Klan against the government," Frost said. "Atlanta had a huge KKK presence at that period of time. They would go to churches at night and tell the pastors they were doing a good job and make a donation to the church. It happened at First Baptist in Atlanta and at churches in Bivins and Huffines."

During this time, Patman had served as a lawyer in Linden, Texas, and then became the state representative for Cass County, as then each county had a representative in the legislature. He had introduced a bill stating that two people robed together would be considered illegal and would be prosecuted, Frost said.

"Neff asked Wright Patman if he would resign as Cass County state representative and become the district attorney for Bowie and Cass counties," Frost said.

In December 1922, a large Klan rally was held in downtown Atlanta, with 150 KKK members marching from Hiram Street through town and ending on West Main, Frost said.

"Over 2,000 people watched this," he said. "It was a 'We know what you're doing' intimidation tactic."

The next year, Patman won the DA seat and dipping the next year went fine, Frost said. Eighty cases were tried and people were put in prison for blowing up the vats, thus beginning Patman's long political career. He was later elected to Congress in 1928 and served District 1 from Texarkana.

The environmental impact of the vats, which were continuously used until the 1960s, is unknown, Frost said. He is known for his knowledge of the area's natural resources and serves on the Region D Water Planning Group. He is also a retired teacher and coach from Maud Independent School District and his son, Stephen Frost, served as Texas' District 1 state representative and was elected in 2004, 2006 and 2008. Frost said his great-grandfather was also involved in Cass County politics and served as state representative in Cass County in 1894 and lost the seat in 1896.

Frost said when the government required the vats, there had to be one every four miles in Cass County.

"The dipping vats went out of style when we started spraying and we found out the dangers of the chemicals," he said after telling of his childhood experience helping his father dip cows in the toxic mix and his skin burning afterward.

After the spraying began, the vats were then simply covered with dirt, Frost said, and the number in Cass County is unknown, as is the number of the sites across the state and country.

"The state that really seems to be on top of this is the state of Florida," he said. "There, there are 3,400 old dipping vats. Now, in the state of Florida, they are identifying these old dipping vats so you won't build a house on it. You also can't have a water well within 1,000 feet of one."

Frost told the group he was unaware of any Environmental Protection Agency action to identify the sites in other locations.