WILSON, N.C. -- In her church, Megan Lively feels safe and loved. Walking in on a Sunday morning, people greet each other warmly. As the men lead services, a few rows up sits her cousin. The assistant pastor is a childhood friend. Even her seat is familiar; she always sits in the back row by the door. She feels safest near an exit.

No one but her family and the pastors know why.

In broad swaths of conservative American evangelicalism, Lively is a famous pioneer, someone whose story of rape as a seminary student and an institutional coverup made national headlines when she came forward in 2018. Evangelical leader Russell Moore calls her a "pivotal" figure in bringing awareness of sexual abuse to the Southern Baptist Convention; best-selling author and Bible teacher Beth Moore calls Lively a "hero."

Here in Lively's hometown, however, most people don't seem to know her story. Her local paper never covered her case. People here almost never raise the issue with her. For years she considered this silence a kind of mercy, protection from the alternative she often received on social media.

"I'm a mom, a wife, a Christian, I love Jesus, and the second I got lumped into #MeToo, it was like: 'Okay, she came forward because of #MeToo, which means she's liberal, which means she's a Democrat, which means she is going straight to hell,' " said Lively, now 45.

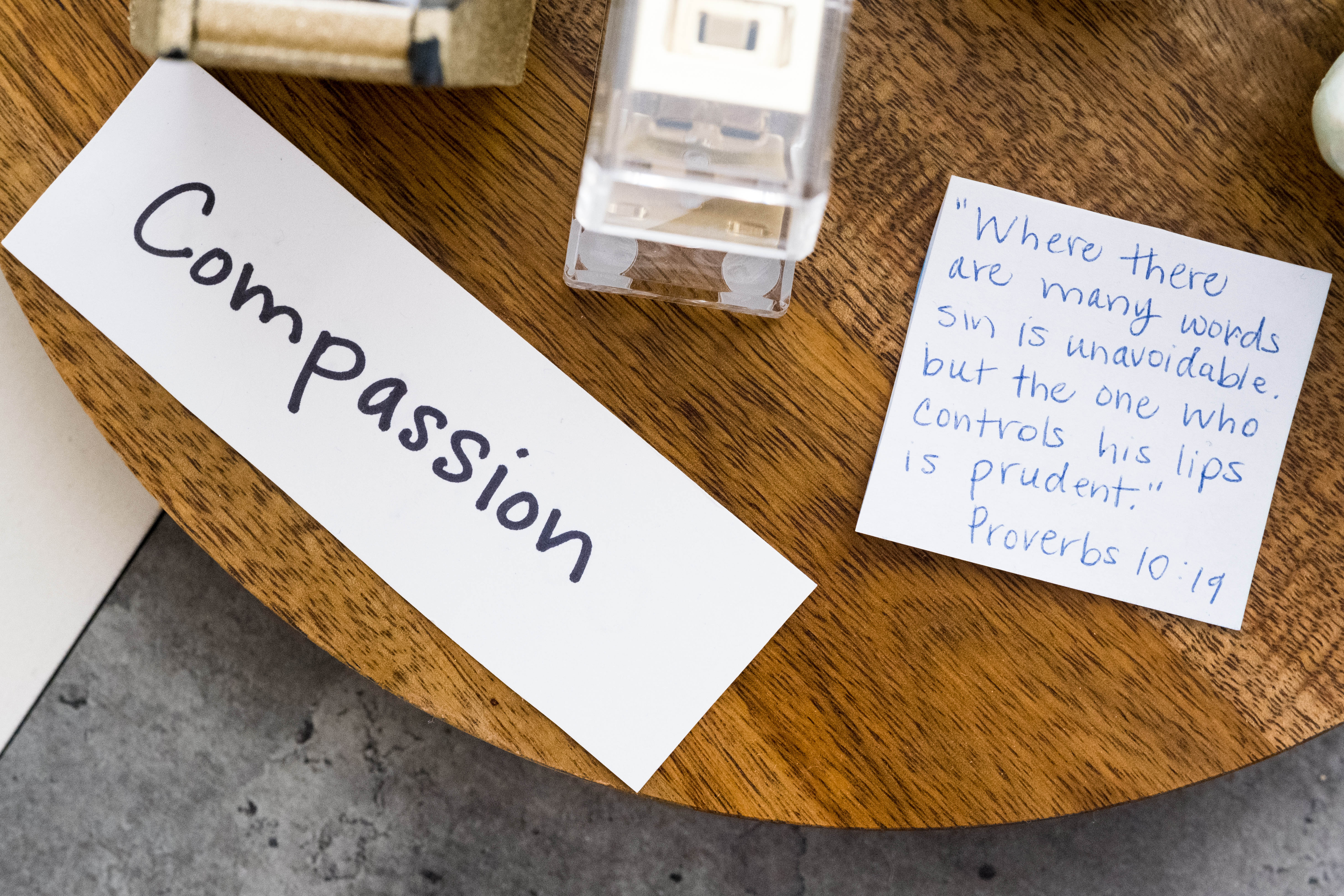

But five years after the hashtag exploded, Lively is testing limits -- her own, Wilson's, and that of a movement about women's voices and power in a religious culture where God called only men to lead. Lively is doing some public writing about what religious institutions need to do to address sexual abuse. She has become a quiet go-to for evangelical leaders when they have questions. And in September, she announced a book contract for "The Cost of Survivorship," whose title comes from "The Cost of Discipleship," a theological classic about the demands of being a Christian.

What are the demands of being a Christian survivor?

Is there room for Lively's belief that the theology banning women from spiritual leadership has often been used to silence survivors? Room to confront conservative Christianity about what it means to treat women well? Is there also room to be a strong, outspoken survivor whose ethos is also bubbly and playful? Can there be #MeToo without being, well, too #MeToo?

"If I'm focused so much on that hashtag instead of people being made in the image of God, my heart will not soften. I'm going to lean into this with Jesus, not #MeToo," Lively said. To her, the movement's emblems are angry female faces -- feisty, justice-seeking types that "I'm not," she said. "I love to think I'm softer and sweeter, you know what I mean?"

Her journey reveals bigger questions about what happened to #MeToo. A September Pew Research survey found most Americans saying sexual abusers are now more likely to be held responsible, but beyond that, it's less clear. A quarter of women told Pew there hasn't been much of a difference. Half of Republican men say they oppose #MeToo. And in Lively's world, this past fall more than 1,200 pastors from the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), the denomination to which her church belongs, signed a petition to ban women from serving in any pastoral role.

Beth Allison Barr, a Baylor University historian who last year published the best-selling "Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth," said Lively may be trying to thread an impossible needle. Theology, she said, is something woven through people's lives from childhood. In this case, Barr said she believes that the theology that keeps women from leadership is shaped by attitudes viewing women as sexual temptations. Women are then saddled with a sense of complicity.

That remains true despite the reckoning Lively helped set in motion, referred to by some as #ChurchToo. After she came forward, the Houston Chronicle and the San Antonio News-Express in 2019 published a report on abuse and coverups in the SBC that identified 700 victims over 20 years. The SBC then approved an unprecedented independent investigation of its executive committee that was released that May. It found that SBC leaders often ignored, minimized and even vilified sexual abuse survivors. The SBC this past August said the Justice Department is investigating multiple arms of the denomination.

"There have been some technical changes, but I don't think it's changed anyone's heart yet," Barr said. "These are lessons that don't disappear overnight just because we changed the rules at church." When cases of abuse arise in religious settings, "there's still this attitude: 'It's not systemic; it's individuals who have sinned,' " she said. "I suspect that has to do with the idea that women's voices matter less."

- -- -

On a recent Friday night, Lively sat in a local brewery with a friend who was yelling Lively's praises over the loud music. They had started talking about her decision to speak out five years ago.

In 2018, Lively told The Washington Post about her 2003 rape at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary and the response of the seminary's then-president, Paige Patterson. As a sexual assault survivor, she was not identified in the story at the time. She recounted how Patterson had her describe the incident in detail to him and to several male seminary students who were his proteges. Patterson told her to forgive the male student, who was expelled, and encouraged her to not report the rape to police, Lively said. She was put on probation for two years because, she thinks, she had allowed the male student into her room.

After the story ran, Patterson, an iconic figure in modern SBC history, was swiftly demoted and then fired from his position at another seminary.

"You got him! You nailed him!" Lively's friend yelled to her through cupped hands. She grinned and pumped her fist.

Lively smiled weakly.

"I didn't want Patterson to be fired. I just wanted women to know," she said later. "I don't wish harm on anyone."

She doesn't like articles about what happened that seem to celebrate the fall of Patterson, who -- as an influential figure in the SBC, the nation's largest Protestant denomination -- is credited with consolidating conservative power and beating back any shifts toward liberalism.

An attorney for Patterson in 2018 said Lively in 2003 "confessed to consensual" sexual conduct and "referred to it as a sin on her part."

At the same time, she feels rattled by the public vitriol earlier this year against actress Amber Heard, who accused her former husband, Johnny Depp, of abuse. Depp successfully sued Heard for defamation. Lively also notices that the billboard they see when they go to the beach that used to say "I Love You. -- God," now says "#MenToo."

Growing up, Lively dreamed of studying at Southeastern seminary. Her goal: become a mom who could teach her children the Bible well. Inspired by a loving pastor she had, she felt called to ministry of some kind. She became a college religion major, then started working on a master's of divinity with a concentration in women's studies at Southeastern in 2002.

After her sexual assault in 2003, Lively sealed up the experience in her mind, telling almost no one and denying to herself that what had happened was rape.

After leaving the seminary in 2005, Lively said, she abandoned the idea of any kind of ministry because of her shame. She moved back to Wilson, opened a social media firm for local businesses and worked for a time for the local Chamber of Commerce. She married Vince Lively, who had also grown up in Wilson. She kept her head down for a decade, building her firm and raising a family.

In the mid-2010s, American women's accusations of sexual misconduct and assault reached a crescendo. Female gymnasts in 2016 began accusing former U.S. national team's doctor Larry Nassar of abuse; dozens of women came forward in 2017 against film producer Harvey Weinstein.

In early 2018, clips began circulating of Patterson, years earlier, counseling physically abused women to stay with their husbands and pray, calling out female seminarians he said weren't doing enough to look pretty, and describing himself ogling a 16-year-old girl's body.

That's when Lively decided to go public, and to do so strategically, using her professional skills with social media and crafting public images. In a tweet naming herself as the unidentified sexual assault survivor in the Post article, she included a photo of her family looking away from the camera, on a beach.

That image, she believed -- of a blonde woman with a husband and two kids, all White, a stereotypical ideal Christian family -- would be more likely to trigger emotion and action in her community of conservative evangelicals than an image of a non-White family or single mom.

"I knew if these men in Texas saw this 'perfect' family in their mind -- I purposely did that," she said. "It's sad it worked."

Patterson was fired two days later.

That began a delayed period of trauma for Lively, just as #MeToo and politics were colliding in the culture wars of the Trump presidency. Lively was receiving loads of critical messages on social media, and even members of her immediate family questioned her account of what happened in 2003. Being even remotely lumped into #MeToo in her community felt like flirting with excommunication.

Lively spiraled. She said she drank too much, felt enraged, and at one point pondered how to drive her car off a cliff, or into a wall. She spoke to a local reporter who felt Lively was still too traumatized to quote.

Beth Moore, who left the denomination entirely in 2021 over the handling of issues including abuse, said in an email that "the price Megan paid to protect and defend other women was astronomical."

Slowly, Lively began to crawl back. Her pastors, she said, never questioned her and instead cried and prayed with her and Vince. They reserved a single bathroom just outside the sanctuary door so she could sit there during Sunday services when she felt a panic attack might come on. Her mother-in-law would tell her God doesn't want her to hide anything and loves her just as she is. She saw mental health professionals and began using EMDR, a therapy that has patients interact with images, sounds and sensations while they think of traumatic experiences, as a way of emphasizing the difference between the present and the past.

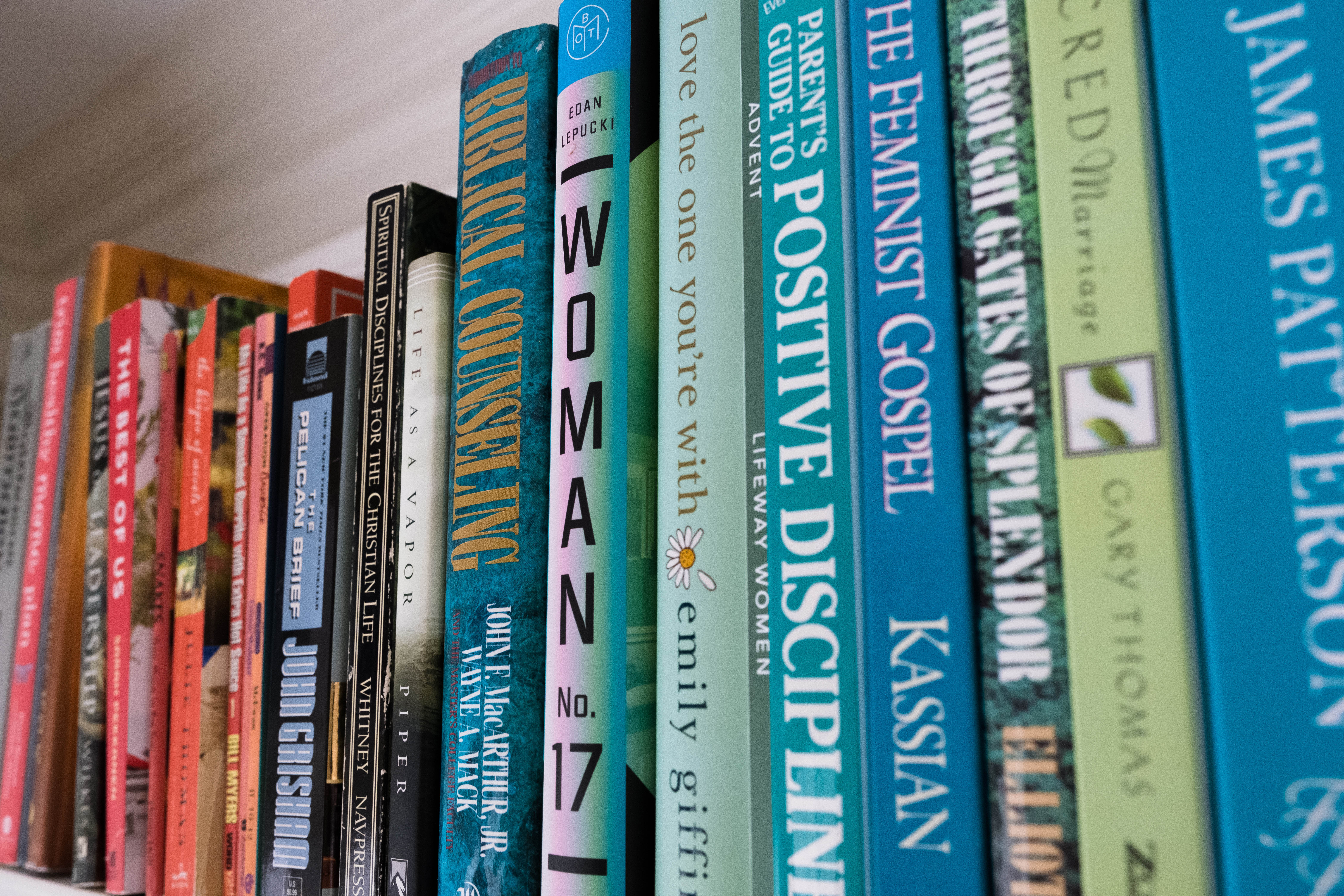

That old calling to some kind of ministry returned, and in 2019, Lively officially switched her business to helping churches with social media. She began diving into the new crop of popular books by evangelical women critiquing the modern institutional church's reaction to various issues: mass shootings, gender roles, abuse in families. She decided, with writer Abby Perry, to create the kind of book for abuse survivors she wishes she had.

- -- -

Lively is still trying to integrate these parts of herself. She often praises humility as a merit, but she sometimes finds keeping silent devastating, like when she recently overheard a prominent person in Wilson ask what an abuse victim had been wearing. Or another local person casually dismiss a sexual abuse accusation as a lie.

Brad Perry, the outreach pastor at Lively's Peace Church, which allows male pastors only, said most people in the congregation probably don't know Lively's story. He wouldn't speak about it publicly without her permission, he said, and she's not the type of person who would try to draw attention to herself. "She wants to show grace through it all. She always said she wants to lift Christ up and redemption and even forgiveness."

But why should Lively have to worry about how she comes across? That's the question for Cambron Farris, a local artist and friend to Lively. "She felt she had to remind me, she's not about #MeToo, and I kind of thought: Is that her defense mechanism? That should be the last thing on her mind. Is that still a form of discrediting of what she's trying to do?" Farris said.

Rachael Denhollander, an attorney and Christian advocate who was the first survivor to speak out against Nassar and now advises the SBC task force on the topic of abuse, said she is also very deliberate about how she presents herself in the church. Low ponytail. Pastel colors, not power colors. Shirt sleeves to the elbow. Neckline to the collarbone.

"All the steps we go through to be calm, submissive, meek women," Denhollander said. Waiting for the pastor to put his hand over my head, [to say]: 'She has my permission to speak.' There are all these calculations. I shouldn't have to do that, and it's not more godly to be that way."

The hashtag #MeToo stirs complicated feelings for Lively, with its various cultural and political connotations. To her, it comes with words like "empowered" and "celebrate" that don't feel quite right.

"It never occurred to me I was part of anything with that label. I just came forward and told the truth. I was never compelled or strengthened by the hashtag," she said.

But every church abuse survivor feels differently, she's learning now as an adviser.

Some people -- like her -- need to hear Scripture. Others not only don't want to hear it, but also would be hurt by it. Never tell another woman what to think about #MeToo, or about choosing to press charges.

"I listen for a long time. I listen until the survivor stops talking. So many people get that wrong," she said.

She does public writing when asked, and she thinks it will be constructive. She said she believes her race and family structure means more people who need to hear her will listen.

"People listen to me. Not because I was sexually assaulted in a church and there is evidence, but unfortunately evangelical men will listen because I'm married; I'm whole in their minds."

Lively now has a tool kit of techniques she uses to keep herself strong and on the mend. For hip pain due to stress, there are standing stretches she does often. For staying present in her body when feelings of trauma wash over, she rubs her forearm. And she still looks for seats near an exit.