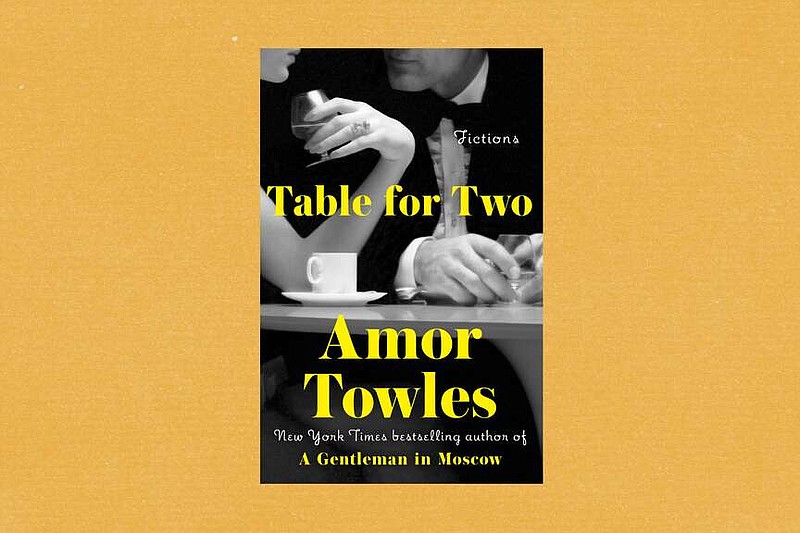

Table for Two

By Amor Towles; Viking. (451 pages, $32)

For all of Amor Towles's literary strengths, he hasn't shown much interest in character transformation. America's favorite Russian patrician, Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov, begins "A Gentleman in Moscow" in a similar frame of mind - whimsical, unbothered, "a natural-born host" - as he ends it. Duchess, the urbane rascal in "The Lincoln Highway," fails to learn a single lesson despite the world's insistence on teaching him.

This is less a slight than a simple observation of a style - and one that comes with perceivable benefits. Most notably, Towles's characters hit the page like fully sculpted marble: frank in their behavior, obdurate in their morality and, by and large, very good-looking. In his newest work, "Table for Two," a collection of six short stories and a novella, Towles thrives at the crossroads of form and technique. There's not enough room for a character to really mature in 30-odd pages; luckily, Towles doesn't need them to.

The collection's title derives from the nature of its conflicts, most of which culminate in heated one-on-one conversation. These stories are straightforward in action but resolve at subtle ethical angles, and they come divided into two geographical sections: "New York" and "Los Angeles." "The Line," the opening story, takes place in post-revolutionary Moscow but concludes in "the middle of Times Square, where the street signs flashed, the subway rumbled." Delivered thus to Towles's stomping grounds - he worked for about 20 years at a Manhattan investment firm and still lives in the city - it's in the Big Apple where the five other short stories remain.

Pushkin, the protagonist of "The Line," stays in New York because he spent all his savings on four-course ocean liner dinners while his wife lay sick in their cabin. "Oh," she thinks at the American passenger terminal, "how sweet had been the notion that her husband had been transformed; that after decades of aimlessness, he had proved to be a man of purpose and imagination; and that her judgment in marrying him had not been so misguided."

If "The Line" shares DNA with "A Gentleman in Moscow," the next story, "The Ballad of Timothy Touchett," is an early high point that finds the author in uncharted territory. Towles, unlike many novelists, has not cast writers in primary roles. Enter Touchett, "his bachelor's degree from a well-regarded liberal arts college firmly in hand," set on becoming "a celebrated novelist."

Alas, the aspirant's literary heroes - William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, Fyodor Dostoevsky - led lives of wondrous adventure. Dostoevsky had even "been put on a train and shipped to the actual Siberia." Touchett's parents, meanwhile, "hadn't even bothered to succumb to alcoholism or file for divorce."

"Oh, what crueler irony could there be," Towles writes, "than for the gods to infuse a young man with dreams of literary fame and then provide him with no experiences?"

Towles writes a writer quite well, forcing Touchett into a Faustian bargain involving vintage books.

Simultaneously, Towles cautions his peers against drawing too close to their source material. "Like parents," he adds in an aside, rapping his knuckles on the fourth wall, "authors have no business attempting to relive their glories or redeem their sins through the lives of their creations. Authors must learn to stuff these burdens in their kit bags and lug them up the trail themselves."

Towles largely skirts the "trail" of that most famous tête-à-tête: marriage. For a collection titled "Table for Two," with a wedding ring featured prominently on its cover, these stories aren't as conjugally inclined as one might imagine. In "Hasta Luego," we're told of "the compromises of marriage," which "govern when, what, and how you eat." But the marriage at stake, after a horrific day of airplane travel and some late-night shenanigans at a hotel bar, belongs to someone other than the protagonist. The same goes for "I Will Survive," where we find a 68-year-old second husband lying about his squash schedule.

Towles's work has always focused on the interior, and not just the rooms of gilded Russian hotels. He's interested in what makes people tick. And he's most interested in the desires of those with material surplus, the purportedly worry-free: The Yale Club makes multiple appearances; we meet "a ten-year-old boy dressed like T.S. Eliot."

"No one is born pompous," Towles reminds us, as if excusing his subject matter. "To attain that state requires a certain amount of planning and effort."

"Table for Two" comprises Towles's first published short stories, but he has said that he "honed his skills" in the medium, and it shows. The only place where "Table for Two" falters is in the novella that closes it, "Eve in Hollywood."

"Fine-figured, with sandy hair, elegant and self-possessed," the Eve of the title is Evelyn Ross from Towles's "Rules of Civility," who here arrives in Los Angeles after a breakup in New York. "Eve in Hollywood" has strengths - it's a winsome portrait of early Los Angeles circa "Gone With the Wind" - but it lacks the breezy impetus that makes the shorter pieces fly. Elaborate backstories are introduced to paper over a couple of plot points, and despite drama involving scheming paparazzi, the tone can sometimes feel cloying. ("How does one fend off the influence of a summer day? You start by serving tea at three in the afternoon.")

By this point, however, "Table for Two" has more than delivered. This collection is not just spare pieces to tide readers over until Towles's next novel. It's a worthwhile addition to his growing oeuvre.